Written by Eric Bronson

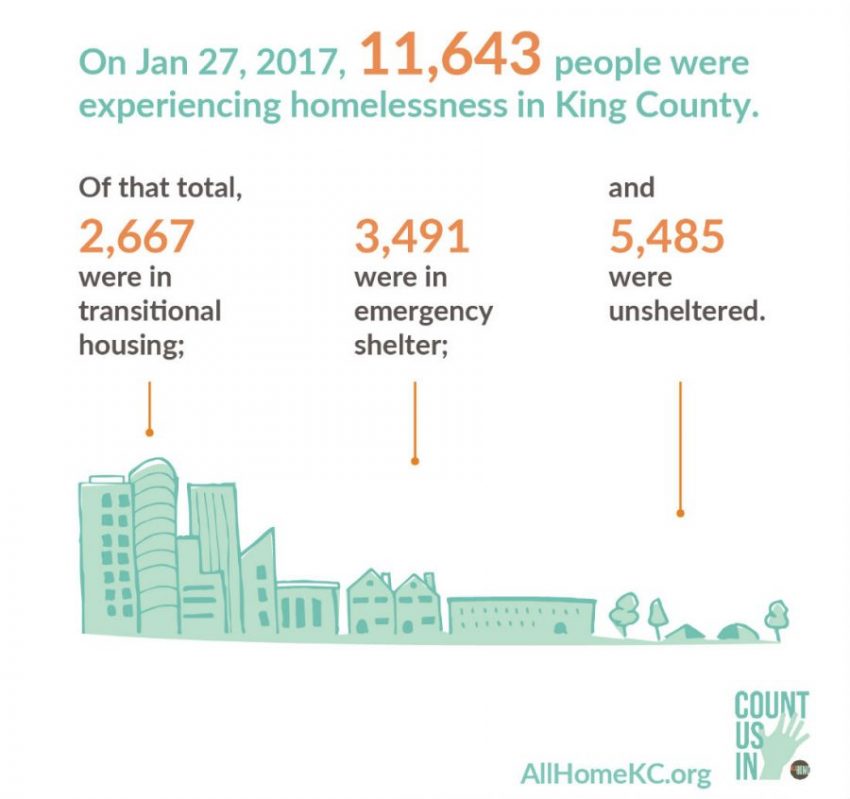

On May 31st All Home King County released their 2017 “Count Us In” Point In Time Count, previously known as the One Night Count. The count, which was conducted across King County on the night of 27th of January, found 11,643 people experiencing homelessness. Of that number, 5,485 were unsheltered, sleeping in places not meant for human habitation. All Home has radically changed the way that they collected the data this year, and have cautioned making apples-to-apples comparisons with previous years’ results. Regardless, it is clear that homelessness remains the reality for an inhumane number of our neighbors. One of the ways in which All Home changed their methodology for this year’s count was to dramatically increase the number of hired paid guides with either recent or current experiences of homelessness. These guides were able to help identify key areas where unsheltered individuals were likely to be, as well as properly and respectfully count those sleeping outside. This enabled All Home to create a more accurate count, and sets a “new baseline for Seattle/King County.”

The single most important change made in this latest count was the expansion of the survey component to include all types of people experiencing homelessness. In the past, All Home had only surveyed youth and young adults. Count Us In 2017 now includes survey responses from a wide cross-section of individuals, and has been analyzed both in aggregate as well as by the subpopulation groups defined by the federal government: those experiencing chronic homelessness, families with children, veterans, and unaccompanied youth and young adults. This survey data, taken in conjunction with the City of Seattle Homeless Needs Assessment performed in late 2016, helps us to gain a clearer picture of just who is sleeping on our streets.

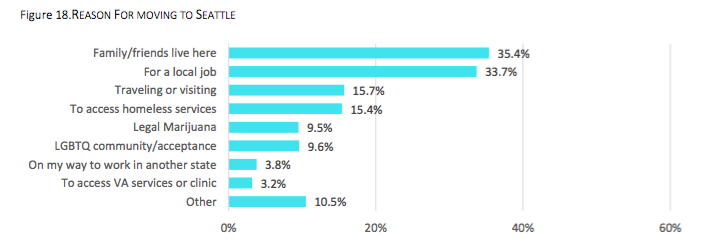

The survey gives those who experience homelessness a chance to tell their own story, and also can help dispel commonly held stereotypes about them. Widely held and perpetuated myths such as “Freeattle,” or the idea that people travel to Seattle to receive services, are debunked by the data. Of those surveyed, 77% were living in King County before they lost their housing, while only 9% were residing out of state. In the 2016 Homeless Needs Assessment, individuals who aren’t originally from Seattle were asked why they moved here, with the most common answer was that they moved to join a social network (35.4%), followed by 33.7% who said they did so for a local job.

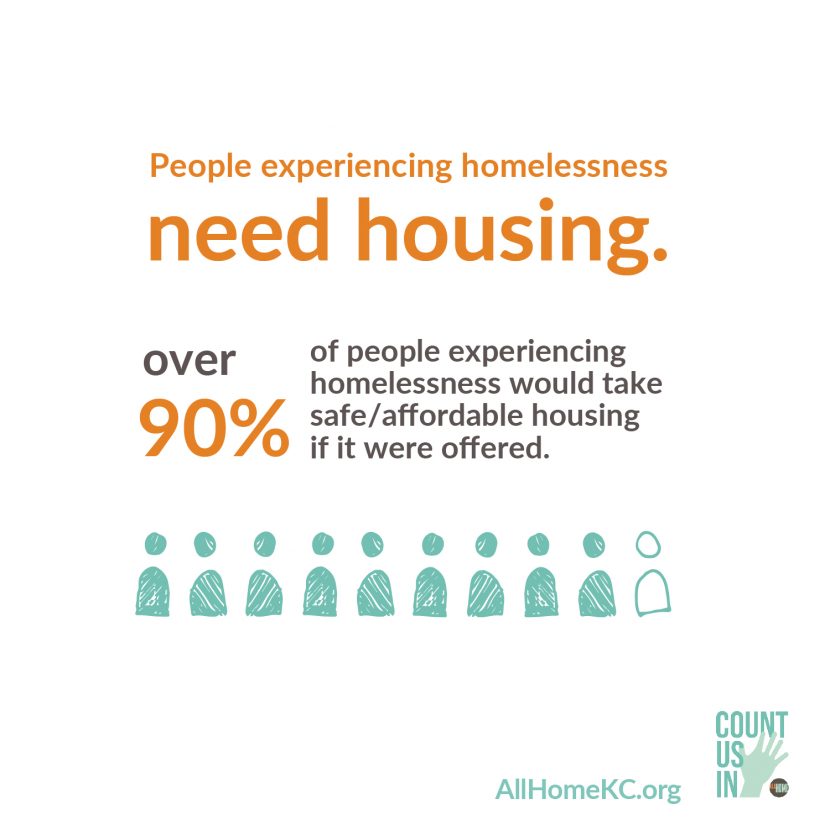

Another myth about those who experience homelessness is that they want to be homeless, or that homelessness is a choice. This stereotype manifests itself in a multitude of ways, such as in toxic attempts to separate “the truly homeless” from “travelers,” who are typically younger and more mobile within a city. It also can be found in arguments made by some that homelessness can’t be solved through services and housing, since those experiencing it won’t want to accept them. In both the Count Us In and Homeless Needs Assessment surveys, over 90% of respondents said that they would move into safe and affordable housing if it were offered.

Another myth about those who experience homelessness is that they want to be homeless, or that homelessness is a choice. This stereotype manifests itself in a multitude of ways, such as in toxic attempts to separate “the truly homeless” from “travelers,” who are typically younger and more mobile within a city. It also can be found in arguments made by some that homelessness can’t be solved through services and housing, since those experiencing it won’t want to accept them. In both the Count Us In and Homeless Needs Assessment surveys, over 90% of respondents said that they would move into safe and affordable housing if it were offered.

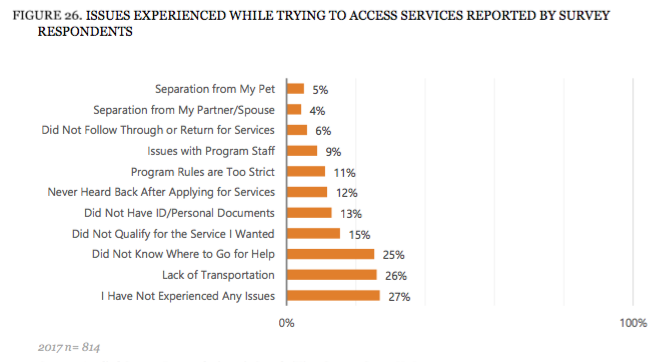

Perhaps the greatest myth of all when it comes to homelessness is that some people are just “service-resistant,” that they are unwilling to use the services offered to them because of an inherent disinterest in receiving them. This is a narrative you can expect to hear at least once in the debates leading up to the Seattle mayoral election. Let’s be clear: people are not service-resistant, services are people-resistant. When asked by the Count Us In survey, respondents reported a variety of barriers in the way of those trying to access services. A lack of transportation and confusion of where to go for help topped the list of issues. Likewise, rules preventing individuals from accessing services with their pet or partner formed a common set of responses.

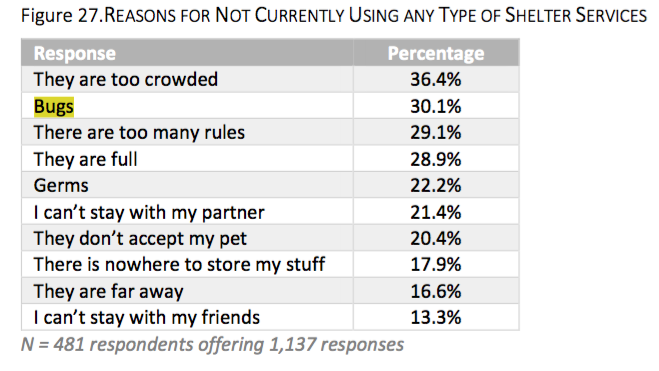

This similarity among barriers shows up in Seattle’s 2016 Homeless Needs Assessment, which asked respondents specifically about why they didn’t use shelter services. Common responses in this table match closely the ones given in 2107 by Count Us In participants. After barriers related to space and comfort (too crowded, bugs, shelters are full), rules that prevent shelter habitation by couples, friend groups, or pet-owners are some of the top constraints. The social or emotional support networks of friends, pets and loved ones are critical to those experiencing homelessness. When services present barriers to the continuation of that support, it is no surprise that people will turn away from the service. By removing restrictions on pets and partners, low barrier shelters and “Navigation Centers” work to ease homelessness effectively by bringing their services in line with what people need. The Navigation Center in San Francisco also addresses the problem posed by storage, allowing residents to securely store their possessions on site.

While these surveys provide us with important contextual data, they also highlight the extraordinary importance of hearing the voices of those personally experiencing homelessness. As we move into the summer campaign season for the Seattle mayoral candidates, it becomes our duty as advocates and constituents to ask the candidates what their plans are for addressing homelessness in King County. And to ask them if they’ve talked to anyone experiencing homelessness. With the help of surveys from point in time counts like Count Us In, we can push back on the myths and false narratives that the candidates or other constituents might peddle about homelessness. Furthermore, understanding how current services fail those who need them by erecting barriers can empower us to show candidates why solutions like Navigation Centers are uniquely suited to address those failures. Let’s commit to hold our potential future mayors accountable to the lived experiences of the 11,643 King County residents who need our help and our understanding.