Everyone counts, even community members that are experiencing homelessness. In this series, we explore the importance of the homeless counts that take place in every county and hear from many of the volunteers that help count. Not all counts are the same. Some occur in the darkest, earliest hours of the morning, and others take place in daylight. Catherine from the Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness takes us through some of these differences and shares her experience at the Point in Time Count in Snohomish County.

Written by Catherine Hinrichsen, Project Manager, Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness, hinrichc@seattleu.edu

We count shapes under blankets in doorways. We count shadows cast by the freeway lights. We count fog inside a car window. During the One Night Count of homelessness in King County, Washington, volunteers don’t talk to the people they count, because most of those people are asleep. We are told to be respectful of that fact.

Our 900 or so volunteers go out into the streets from 2-5 a.m. In those few hours we get a tiny glimpse into what it’s like to try to find a place to sleep outside in the cold and rain, night after night.

Sometimes the volunteers find people walking around, or riding the bus all night. The volunteers still don’t talk to the people they count. They make a mark on a chart.

But in the other 3,000 cities and counties taking part in this count nationally, it can be very different. The Point in Time Count (PIT) in other regions, such as Pierce and Snohomish Counties in Washington state, is conducted during the day and evening. Workers, many of whom are volunteers, conduct face-to-face interviews with people who are homeless, using a questionnaire. King County this year also used this approach to conduct its third youth & young adult count, “Count Us In,” aligned with the One Night Count for the first time.

The One Night Count street count volunteers do the count on foot, walking through the areas they’re counting, using defined mapped areas, whereas the PIT count interviews are conducted at a centralized location, or via outreach. The centralized sites might be a church, a nonprofit, or a community feeding program. Or, workers and volunteers might drive out into the community to search for people where they’re seeking shelter – in a car, a tent, or an encampment in the woods.

In both cases, volunteers might have to make a judgment call about whom to approach or whom to count, not succumbing to stereotypes about homelessness in the process.

The difference, as they say, is night and day.

Important advocacy tools

Both the One Night Count in King County and the Point in Time Counts elsewhere are not only important means of collecting data. They are advocacy tools that move the community to take action.

But when we visited two of the four PIT centralized count sites in Snohomish County on Jan. 24, 2013, I learned something important about the daytime counts. That face-to-face data collection by volunteers gives them a personal connection to the people they are helping.

That personal connection can be very powerful, perhaps in a different way than the equally striking experience of doing the One Night Count.

Collecting volunteer stories

We had been tasked with collecting video stories of volunteers working on the count in Snohomish County, Wash., north of Seattle. Judy Pansullo, a grad student in Nonprofit Leadership and a veteran filmmaker, was the director, producer, photographer and sound technician all rolled into one. Perry Firth, a grad student in Community Counseling, asked the questions and added the perspective of an experienced Crisis Line volunteer. Perry also did the One Night Count that night and wrote about it from that perspective.

The impact on volunteers

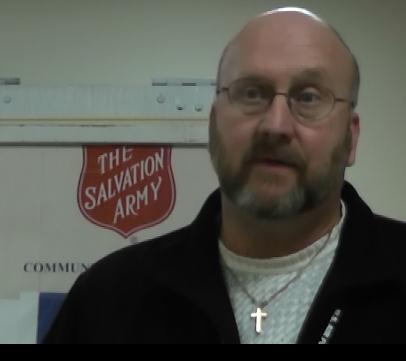

Volunteers on both the night and day counts may see things that surprise them or sadden them. The degree to which they are affected may depend on whether they work as a provider or are totally new to this kind of experience, said Jerry Gadek. Jerry is a Point in Time Count volunteer who trains other volunteers in Snohomish County from the central Everett location at the Salvation Army.

Jerry, who works for Snohomish County Human Services, said that for the volunteer who already works in the nonprofit world, or who has done it before, the training is on technical aspects and on anything that might have changed for this year.

But for the person doing it for the first time, “a lot of the training time is on what they’re about to experience. It is one thing to step forward and say ‘I really want to give this a try’—but when you walk away from that first mom, that 22-year-old with the three-year-old child who’s trying to stay warm in the car in the [name deleted] parking lot, when you walk away from that for the first time and you don’t do this for a living, it is extremely difficult to go on.

“So we spend a lot of time preparing them for what they’re going to see and the fact that they’re not going to be able to fix anything today.”

Jerry said the de-briefing for volunteers afterwards is sometime more important than the training beforehand.

You can see a video of Jerry talking about the volunteer experience on Firesteel soon.

Read about self-care for Point In Time volunteers here.

The PIT Count volunteers also see the faces of the people they are counting, and sometimes they see etched on those faces the stressful life of homelessness.

Everett volunteer Cherisse Webb, who works for Catholic Community Services coordinating volunteers for their chore service, had just conducted her first interview when we talked to her, and she was still a little taken aback. “I interviewed a woman who looked like she might have been 60. I found out she was 45.”

Talking to volunteers on the PIT Count Day: What motivates them

What motivates all these volunteers, who are so crucial, to do these counts?

Our first stop was at the south Snohomish County site, the Good Shepherd Baptist Church in Lynnwood, about 17 miles north of Seattle. The coordinator, Maria Bighaus of the YWCA Seattle | King | Snohomish, said this was the first year the count had been done in a south county location, in an effort to reach more people.

In a back room, volunteers did the interviews, served food and even ran a table where people could do therapeutic art.

Some of the volunteers have worked on this for years and even in both types of counts; for instance, we met Candace Pidcock, who had just moved from King County, where she had volunteered for the One Night Count for years.

Candace worked as a domestic violence advocate in King County for 10 years before moving to Snohomish County. She told us, “I know how important it is to have affordable housing” for women in a domestic violence situation, and that drives her to volunteer.

Many volunteers work in social services, like Candace and Cherisse, and fall into the category Jerry described—those who are familiar with the issues around homelessness.

Others were first-timers who were recruited through various outreach, or saw the announcement sent out by Snohomish County Executive Aaron Reardon.

First-timers tell us why they volunteered

Before they set out, some of the first-timers talked to us about their expectations. They expressed curiosity, enthusiasm and sometimes a little fear or anxiety. Felicia Cain, a student at Edmonds Community College, said that she’s interested in this kind of work because it is related to the work she wants to do someday as a nurse. Another, Nakahish, told us, “I’m just doing it because I want to help people.”

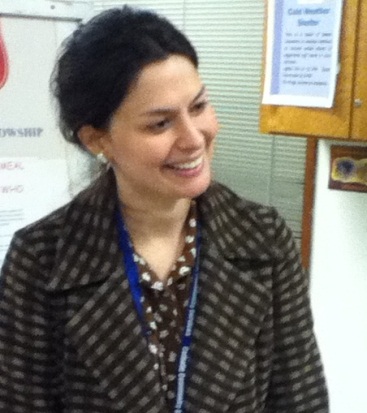

Out in the church lobby, there was a sitting area with some comfortable armchairs. The Lynnwood PIT Count coordinator, Maria, a lovely woman with curly dark hair who exudes warmth and caring, had been talking there with some men who were dressed for cold weather – coats, wool hats, sweatshirts with the hoods pulled up, most with full beards. It’s never appropriate to make an assumption about who is homeless, but as it turned out, these were indeed men living on the street.

Nearby, a group of about 10 or 12 volunteers were assembled, other students and instructors from Edmonds Community College. These were all first-time volunteers who would go out into Lynnwood to do interviews. They stood and listened as Maria described some likely places to find people to interview. The armchair guys chimed in with helpful suggestions.

“Try the A&P,” one of them called out. “Or the Pay ‘n Save.” (Note: these names are changed for privacy reasons.)

As the volunteers were deciding how to split up into groups, the guy called out again, “You’re crazy to do this, you know.” There was an open seat next to him, and I slipped into it. He was wearing a name badge that said “Saber.”

At one point, Maria told the armchair guys that this count was a way to get help for them. “I don’t want to see you here again next year,” she said, partly teasingly but at the same time very serious. She wants them to get housed.

Saber said, “Where are we supposed to go?”

The volunteers left and I stayed and had a conversation with Saber and the others. It is a story for another day, but for me, it was a personal connection that totally changed the way I look at everyone experiencing homelessness.

Starting Friday morning, the results come in

In King County, we get results from the One Night Count in mere hours after the count is over. People who didn’t do the count and who are awake and paying attention to news and social media can usually find out the number a few hours after it’s over.

By the time most people began their work day, we knew that there were 2,736 men, women and children homeless and sleeping outdoors in King County in the early morning hours of Friday, Jan. 25, 2013.

Around that time, a group led by Real Change’s Tim Harris gathered outside Seattle’s City Hall to ring a gong for every person counted: 2,736 strikes of the gong this year.

In other counties, the data takes longer to process. Preliminary data, like this reported from Snohomish County, are available in days. More detailed analysis can take weeks. For example, Breanne, the volunteer in Everett, said on the day of the count that she and the other organizers wondered how the numbers might be affected by the new anti-camping law in Everett city limits; perhaps people might be pushed out of the city into other areas of the county.

King County’s HMIS information isn’t counted during the One Night Count; it’s compiled via Safe Harbors by emergency shelters, transitional and permanent housing and providers.

All the data is compiled into the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) used by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) and others for funding decisions at the local, state and federal levels.

Keeping an eye out for people on the street

Late that Point in Time day, in Everett, a volunteer named Kevin Marshall told us about a woman who is homeless whom he’s been seeing for a while regularly in either one location or another, just sitting there, hour after hour. He thought he recognized her from somewhere, and realized, after seeing her several times, where he knew her from. The connection is so striking that I wish I could share it; it has to do with his children’s entry into the world. And now she’s on the street. He said he keeps an eye out for her. If he doesn’t see her in one of the two places, he worries about her.

It’s that type of personal connection that fuels the Point in Time Counts and keeps volunteers coming back.

Next week Firesteel will feature a video of Snohomish County volunteers like Breanne, Felicia, Kevin and others talking about why they worked on the Point in Time Count.