Written by Lindsey Habenicht, Seattle University student and project assistant, Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness

Wandering around the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., and trying to find the building where I interned for the summer, I passed by eight people on the streets. A cacophony of voices—begging and pleading for someone to help—overwhelmed me, as did my inability to help them on my own. I had been in the District for less than 24 hours and already witnessed the plight of people who are homeless in excruciating detail. No matter where I walked, I continued to hear the same calls:

“Excuse me, do you have any change?”

No, I’m so sorry.

“Do you have any food?”

No, I’m so sorry.

“Do you have an extra dollar for the metro fare?”

No, I’m so sorry…

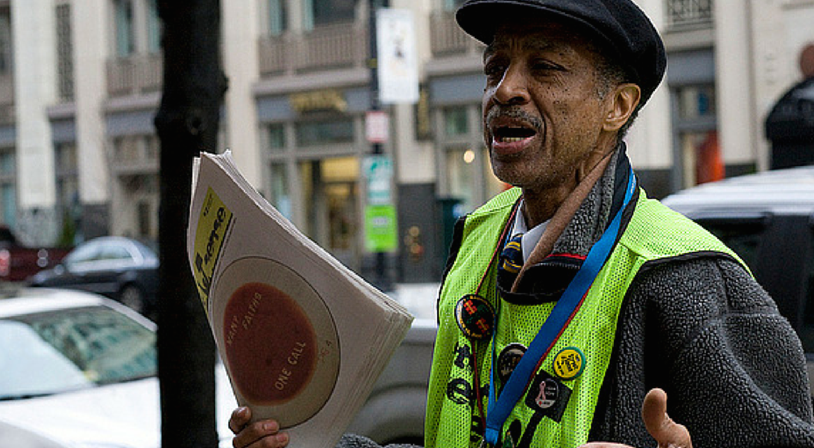

“Street Sense! Get your copy of Street Sense,” I finally heard. “Help the homeless help themselves. This is not a hand out, but a hand up!”

I walked into the historic Church of the Epiphany, the Street Sense headquarters, only a few yards from where the vendor had been selling the paper.

Street Sense is Washington D.C.’s street paper, very similar to Seattle’s Real Change. Working to elevate voices on issues of poverty and injustice, the organization creates economic opportunities for people experiencing homelessness. Vendors pay 50 cents for each paper to cover publishing costs, and then distribute the paper for a suggested donation of $2.

In the lobby were two people who would become my very dear friends: Patty and Morgan. Only moments into our initial meeting, I had heard parts of Patty’s and Morgan’s stories that left a lasting imprint on me. They were so strong, so resilient, so passionate, and so loving. Instantly, Street Sense felt like home— like family. The work at Street Sense was meaningful, and I would have spent every day there if I could.

But because the internship was only 30 hours a week and unpaid, I needed to work on the side.

Two Worlds Collide: Taking on Corporate America

Some days, I was on the staff of a street newspaper in downtown D.C., and other days, I was a salesperson at Nordstrom in a wealthy suburb. Not surprisingly, my values conflicted.

Half of my time was spent with those living on the margins of society, and the other half was spent helping wealthy women dispose of their income, as if it were nothing. It became increasingly difficult for me to bridge the gap.

Washington, D.C. is a place of premier opportunity as well as a place of outstanding poverty. In fact, the District has a larger income disparity than any state in the country, with the top 10 percent of earners making more than six times the amount as the bottom 10 percent.

The Perplexity of Privilege

A woman in her mid-40s, hunched over and tired, walks by me—slowly and staggering—dragged down by the weight of her suitcase. It has a large rip down the front and both wheels are crooked in such a way that the suitcase doesn’t really roll at all. This suitcase is packed so full it looks as if it could hold all of her worldly belongings. She doesn’t look up or utter a word.

Another woman in her mid-40s walks by with a small, chic designer bag hung over her shoulder. The only weight impacting her ability to walk a straight line is from the six shopping bags she grips tightly in her fists. She pompously asks for a taxicab.

These are two very different people who exist in the same world; a world I shared with them over the summer when I met them—on distinct occasions—at Nordstrom. This world treats one of them unfairly, though.

The Woman With the Suitcase

The woman dragging the ripped suitcase said her name was Simmons. She came into the upscale department store almost every day; always tired, always staggering, always in the same long dress and beat-up blazer, and always with her suitcase.

As a disclaimer, I try to refrain from making any assumptions about people’s experiences, but had thought that Simmons may be experiencing homelessness. After all, I worked with people like Simmons many times a week at Street Sense.

Other employees in the store laughed at Simmons. Her tired eyes and excessive baggage confused them; they wondered why she would come to Nordstrom every single day. What a sad life, they’d say, doesn’t she have anything better to do?

I tried to explain that maybe she wants to be here because it’s a better alternative. Sometimes I’d see Simmons in the women’s lounge asleep on the couch. Perhaps, I would tell them, this is the only place she feels she can rest safely.

It wasn’t until my very last day that Simmons and I spoke beyond that of a casual greeting. She had been looking at the same cotton dress—marked at $36—for weeks. She watched and listened intently as other women swiped credit cards for 10 times that amount.

Until this point, Simmons had established a routine: take the dress to the counter, ask me to put it on hold, and never buy it. But when the dress finally went on sale, she brought a fistful of crumpled bills out from her chest pocket. When I asked if she’d need a bag, she said no thank you and stuffed it inside the suitcase.

This woman lives out of her luggage, I thought to myself.

I try to keep the thoughts in my head distant from the expressions on my face, but this time I failed. My heart hurt for Simmons, and she could tell. She knew I wanted to talk to her more, and she knew exactly what I wanted to ask.

“I bring my suitcase everywhere now,” she said. She sounded almost relieved to be telling me her story. “Someone at the shelter sliced it once while I was asleep and took everything. They took everything I had.”

The shelter. I knew it.

Before I could say anything at all, Simmons walked away. I saw customers look at her with unforgiving looks of distaste as she did so.

Really, it was unusual to see someone like Simmons inside Nordstrom—or any corporate giant for that matter—where money and consumption came first, and compassion second.

But Simmons helped me realize why it has always been so hard for me to jump from one world to the next, because the majority of our privileged world does not understand what it feels like to be a second-rate citizen in a first-rate society, and therefore lacks a lens critical to empathizing. They have not had authentic conversations with those experiencing homelessness, and therefore do not understand what put them in this place. Don’t they understand that no one chooses to be homeless?

The War on Poverty, 50 Years Later

On the metro ride home from work, I cried. I was plagued with the guilt that I had a roof over my head, and Simmons did not.

I was plagued further with the guilt that my friends at Street Sense—the ones who worked so hard to make a few dollars each day in a city that lessened the value of that dollar—didn’t know when they were going to get their next meal, a doctor’s appointment, or a place to call their own.

In 2013, President Obama addressed this issue of inequality—the one that sleeps right outside the White House steps—and noted the great challenge of our time, “making sure our economy works for every working American.” He explained that we have stepped into a War on Poverty, fighting an economy that has become profoundly unequal.

He said that, “the idea that so many children are born into poverty in the wealthiest nation on Earth is heartbreaking enough,” but the idea that a child may never be able to escape that poverty should offend all of us enough to the point that we are compelled to act.

While we’ve made great strides in acknowledging ways we can combat homelessness, I spent the summer wishing that the whole country could care about people living in poverty enough to incite movements that mattered; to build monumental changes necessary to create a colorful illustration of the American dream, where equal opportunity is the primary promise.

In addition to income inequality, gentrification has wiped out poor neighborhoods, using the concept of “revitalization” to disintegrate blighted neighborhoods. I witnessed this firsthand when I reported on Barry Farm, a historically black public housing community in southeast D.C. that is facing demolition.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development recently announced that any community receiving federal hosing funding, such as Barry Farm, is required to spend it in a way that “dismantles segregation.” That said, its residents have no safety net: their homes will be demolished, and a mixed-income community will be built in its place. No matter the fight, people living in poverty are preemptively set to lose.

This apparent dedication to mixed-income housing often falls short. Instead of heightening opportunity for economic mobility, it further stresses the livelihood of those who are already impoverished, as low-income housing of the same design becomes almost unattainable. We’ve seen this happen close to home too, with the redevelopment of Yesler Terrace in Seattle.

Running Out of Options

Housing shortages in the District and throughout America make income inequality far worse. When looking for housing for my D.C. internship, I was met with a hard choice: spend the average $3,000/month on housing near a metro station (I didn’t have a car), or go “hostel style” and share a single-sized room equipped with bunk beds for no fewer than four people.

I opted for bunk beds, and soon learned that this room-sharing technique was common practice in the District. My host, a web-developer in his late 20s, said he had no choice but to rent out space in his own home to make ends meet.

Almost everyone I met in the District was room sharing, and still spending obscene amounts of money. Yes, my rent was not for a home, but for a bed. For this bed—a bunk bed in a room shared with up to six strangers—I paid more than the average rent for a studio apartment in Seattle.

This is happening in San Francisco, too, where listings for bunk-bed shares are posted to Craigslist for upwards of $1,000 per month in premier downtown locations.

If housing is so hard to come by, even for those with well-paying jobs who sit at middle-class levels, it’s no wonder that we struggle with homelessness in our nation.

What This Means

My summer experiences blending the privilege of the rich with the cries for help of people who are poor was eye-opening, jarring, and heart-wrenching, and left me with more questions than answers.

- I question why the community-suburb I called home for eight weeks worked so diligently to turn a blind eye to those most in need, and I am determined to ensure my communities here do not do the same.

- I question why our country (the “richest on Earth”) has so much, but we somehow forget that some of our neighbors have nothing at all, and I’m inspired to bring this to the forefront of my conversations with friends, family, and strangers.

- I question how I can be a better advocate for the people I’ve learned to love so much— Simmons, my friends at Street Sense, and others who have touched my life in brief passing—and I will work hard to become one.

This experience gave me new motivation to end homelessness. I now realize what a critical role each person plays in making such monumental change. In speaking with our friends, neighbors, professors, and policymakers, we are setting our nation’s agenda; we are telling the country that homelessness is inexcusable, and something greater must be done to end it.

What You Can Do

- Talk to your friends and family about what homelessness looks like in King County.

- Write to your policymakers and attend city council meetings. Advocate for affordable housing and equitable pay policies. Find out how to contact your Washington legislator here.

- Buy your local street paper and follow them on social media: In D.C., @streetsensedc or streetsense.org; in Seattle, @realchangenews or realchangenews.org.

- Come to a campus event that I helped organize along with other students at Seattle University and University of Washington, Wednesday, Dec. 2, 5 p.m. at Seattle U. Seattle Mayor Ed Murray will talk about the recent state of emergency declaration, and we’ll hear from experts on what we can do. Register here.