Written by Brandy Sincyr, Homeless Student Advocate and Program Assistant at Columbia Legal Services

I started advocating for youth experiencing homelessness when I was 19 after my family and I had endured years of housing instability and homelessness. It was empowering to feel like my experiences were helping build momentum and awareness for youth in similar circumstances. That’s why I was eager to work on “Crisis in Washington State,” a report which describes the number of students identified as experiencing homelessness in Washington.

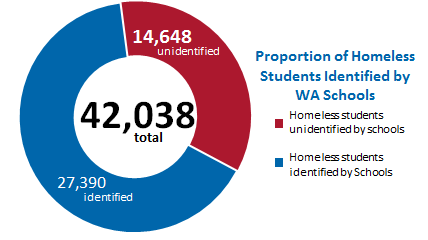

Our report compares the findings of two different state agencies. The first is the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, which identified 27,390 students experiencing homelessness in 2011-2012. The second is the Washington Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) report prepared for the Department of Commerce, “Homeless and Unstably Housed K-12 Students in Washington State,” which used integrated administrative data to identify 42,038 students who experienced homelessness during the same 2011-2012 school year. This report is the first time we have had data from a different state agency that confirms schools are under-identifying students experiencing homelessness.

This gap in identification means at least 14,648 students did not receive the vital resources and protections that ensure students experiencing homelessness receive a quality education.

DSHS’s findings of 42,038 students is enough to fill 584 school buses, and even exceeds OSPI’s most recent 2013- 2014 identification rates of 32,539 students experiencing homelessness. These students are living on the streets, in substandard housing, shelters, cars, motels, or living with others due to economic hardship. The vast numbers of students experiencing homelessness alone is alarming, but it becomes increasingly distressing when you see the poor educational outcomes of these students. Students experiencing homelessness are less likely to graduate than their housed peers. They have the second-lowest high school graduation rate in our state, and compared to their housed peers, they are more likely to fall behind in math, reading, and science.

This hits close to home. When my mother, sister, and I became homeless, my mother marched into my school’s front office and told them what we were going through. I immediately qualified for, and began receiving, services from Washington’s homeless education program. I met with my homeless liaison the next day. My sister on the other hand, had a completely different experience. She changed schools multiple times, lost credits, friends, mentors, and at one point, was temporarily barred from enrolling in school. She never met her homeless liaison. It is unclear if her school was notified of her living status, or if they knew she qualified for resources and protections under McKinney-Vento. With a supportive family and knowledge of her McKinney-Vento rights, she entered an accelerated credit retrieval program, and graduated on time. But not everyone is as fortunate.

When funded, this program works, but it is always going to be tricky. We know from the testimonies of families and children that they are often ashamed or afraid of telling their schools what they are going through, for fear of child welfare involvement or other consequences. They also often do not understand the protections and resources schools can provide. This can only improve with additional funding for our state’s homeless education program, clearer guidelines for mandatory reporters, and educating the families and youth schools serve.

Learn more

- Hear Brandy talk about the report in an interview with KUOW, and read Firesteel’s 2013 interview with her

- Read the “Crisis in Washington State” report

- Find out more about student homelessness in Washington state on the Columbia Legal Services website

- Watch a video in which educators explain how homelessness has affected their students

- Listen to StoryCorps “Finding Our Way” conversations about students’s experience with homelessness