This is the second part of the two-part series, “Separate and Unequal: Poverty, Race and America’s Education System.” Read the first part here.

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

A few months ago I was talking to an advocate working with a Seattle-area school district, one where teachers were struggling with issues of race and class. Or to put it more directly, she was working with the district because it had become clear that the teachers were struggling with implicit racism and classism. The advocate shared with me that the black students she was supporting were referred to the office far more than the white students on her caseload for the same behavior.

Stories like these are important because they bring something that can feel opaque and far away down to reality. Real people are struggling with inequality right now — and not in some distant place. Implicit racism matters, and its effects show up in schools. It is not something created by the PC police designed to make white people feel bad about themselves. It is here, in our community.

So what are we going to do about it?

In Part One, I examined some troubling outcomes of the re-segregation of our nation’s schools, including the disproportionality of discipline that results in suspensions, expulsions and dropping out. These contribute to the systemic problem known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” and lack of success for many students of color. In Part Two, I’m going to talk about the impact of all this and what we can do about it.

The school-to-prison pipeline

Suspension and expulsion are precipitating factors that disconnect students from the stability of school, increasing the likelihood they will enter the prison system. There’s no denying that these procedures often have racial undertones — Hispanic or black children accounted for 70 percent of school-related arrests nationally in 2010.

These arrests are not occurring for violent offenses, either — but for behaviors that fall under the category of “disruptive.”

The degree to which some schools are now using police to arrest misbehaving students is a relatively recent phenomenon, and positions the school to become a literal entryway to the justice system. And, when nonviolent misbehavior is met with prison, schools fail to respond to their students in a developmentally appropriate way.

Not only does this take a toll on a school’s larger culture, according to the American Psychological Association, but frequent use of school-based arrests contributes to a negative learning climate and poor student development.

Hooray! Just what we wanted.

There is rising urgency surrounding the use of suspensions in schools because students who are suspended are at increased risk for school dropout (and then later poverty and criminal activity). In fact, of those students who have been suspended in middle school three times, 49 percent go on to drop out in high school.

The re-segregation of the American public school system

However, it is not just disciplinary systems that harm children of color; America’s complacency around schools segregated by race (and socioeconomic status) does as well. Through interacting factors, including the repeal of court-ordered integration and residential segregation, America has created two school systems: Poor, black and Hispanic students attend one school system, while middle-class white and Asian students attend another. The Civil Rights Project at UCLA notes in their report, Brown at 60, that for Hispanic children residing in the West in particular, segregation from white and middle income peers has become a pressing issue.

Integration was important for leaders of the civil rights movement because it was an avenue toward opportunity for children of color. The best schools were the ones attended by whites — a truth that holds mostly holds true today.

On the push for desegregation, Gary Orfield, the co-director of the Harvard Civil Rights Project,writes “[it] did not arise because anyone believed that there was something magical about sitting next to whites in a classroom. It was, however, based on a belief that the dominant group would keep control of the most successful schools and that the only way to get full range of opportunities for a minority child was to get access to those schools.”

Today, we don’t tend to see “Whites Only” signs in our communities — but with forced integration falling under attack in the 1980s and ‘90s and the Supreme Court finally ruling in the early ‘90s that schools no longer needed to integrate students, this doesn’t really matter. Schools are newly segregated as they have not been in decades.

The repeal of mandated integration correlated strongly with increased re-segregation of black and white students. In fact, between 1993 and 2006, the number of all-minority schools doubled.

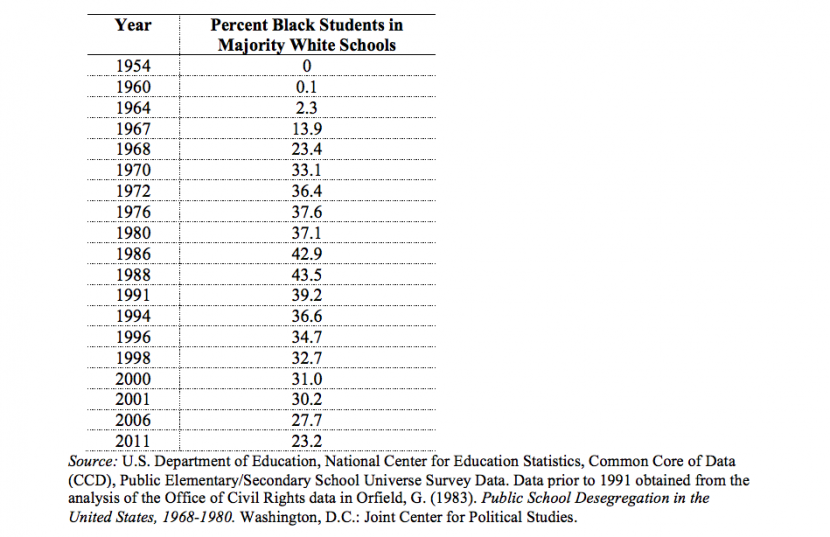

According to the Civil Rights project, by 2011 this meant that all of the progress generated by mandated integration was lost. In the South, at the height of integration, 44 percent of black students were attending schools with whites. After the repeal of court-ordered integration, by 2011 only 23 percent of black students attended schools with whites.

In the table below you can actually see that the percentage of black students in majority white schools has actually been decreasing steadily since 1988, with the number of black students in white majority schools now where it was in 1968, at the height of the civil rights era.

Court-ordered integration was attacked in a series of court cases, but was also a result of a policy shift toward overemphasizing academic standards in student success, rather than race and student background. The sense at the time was that since our country had moved past the time when racism was visibly encoded in law, that forcing schools to have a balanced mixture of black and white students was no longer necessary.

Yet this has not been the only contribution to our re-segregating schools. Another issue has been “white flight.”

In this case, “white flight” refers to white families leaving schools and school districts as they gained increasing numbers of children of color.

For instance, during the ‘90s, school leaders in Tuscaloosa, Ala. were acutely aware of what happened in districts across the state when black students started making up a significant percentage of local area schools: white parents moved to whiter communities or sent their children to private schools. This placed school leaders in Tuscaloosa in the uncomfortable position of realizing that integrated schools sent white people and their money heading for the hills — which in turn left school leaders deciding that if they didn’t create schools with majority white children, their district would continue to lose money.

This thought process led to re-segregation and concentrated poverty for Tuscaloosa’s black children. And it is true for other cities as well.

Today, urban poor white children are far more likely than poor black children to be integrated into middle-income schools where they can reap the benefits of higher-quality instruction, resources and the connections that come from more affluent peers.

Residential segregation contributes to the problem

That black students and white students attend different schools is a result of more than school district policy; it is a result of people living in neighborhoods with people who look like themselves and come from a similar socio-economic status.

So school segregation is also a result of residential segregation, which is itself a result of racist and discriminatory housing and zoning regulations. This residential segregation may also be linked to self-segregation, where people of like races prefer to congregate together.

According to a recent article in The Atlantic, more-integrated neighborhoods could be achieved through housing policies that push back on lenders steering people to communities based on race, and ending zoning regulations that prohibit mixed income housing developments. Apparently cities will do these sorts of things intentionally to attract affluent white buyers.

This is reminiscent of institutional racism, or racism that is larger than the decisions of any one individual. Even goodhearted people who abhor racism end up participating in these policies, to say nothing of the marginalized people they impact most severely.

These practices contribute to facts like these: at least as of 2000, there was a 1 in 10 chance a black person would live in concentrated poverty, compared to 1 in 100 for a white person in urban areas.

Benefits of integration

The fight for opportunity and a level educational playing field is worth fighting because we know that schools which are integrated along race and class lines provide benefits to all students, including:

- Increased understanding of different cultural and racial experiences

- Increased social cohesion

- A stronger belief in democratic values

- Increased math achievement scores of black and Hispanic students

- Increased Hispanic student success; of those Hispanic students who attend elite colleges and are thriving academically, 70 percent have attended desegregated schools

- Increased likelihood of cross-racial friendships (which has been linked to decreases in implicit racism)

Further, other researchers have found that the socio-economic profile of a school can have a large impact on student learning, regardless of student background in some cases. Thus, “on average, low-income students attending a middle-class school perform better than middle-class students attending a low-income school,” according to the Kirwan Institute.

And court-ordered integration greatly benefited black students, doing everything from raising test scores to generating improved health.

Unlike those students reaping the benefits of middle-income schools and racial diversity, poor students of color attending low-income schools contend with issues like:

- Reduced course offerings: Of schools that enroll primarily black or Hispanic students, one fourth don’t offer important college prep courses like Algebra II, and chemistry is not part of the curriculum in one third of those schools.

- Less integration: Urban poor white children are far more likely than poor black children to be integrated into middle-income schools where they can reap the benefits of higher-quality instruction, resources and the connections that come from more affluent peers.

- Increased spending on white students: An average of $733 more is spent per pupil in schools which are over 90 percent white than in schools where that is not the case.

- Less per pupil spending as black students rise in the school population: “A 10 percentage point increase in students of color at a school is associated with a decrease in per pupil spending of $75.” The author of this American Progress report notes that while this may not be linked explicitly to racism, it has the effect of further marginalizing students of color.

Dr. Martin Luther King once talked of black segregation as “a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” Schools that receive less money for poor students and students of color contribute to that lonely island of poverty. Schools that are unable to offer the advanced curriculum and classes required for college (like algebra) do, too. Students cannot learn what they are never taught, or benefit from resources that are never given to them.

Last but not least, the connection to family homelessness

One of the reasons education and the factors that influence school success are important to contemplate is because school provides an avenue to the middle class. While there are certainly those who manage to be successful who, say, have dropped out of high school or failed to attend college, for many students these sorts of outcomes limit their options in ways both large and small. Students who drop out cannot access 90 percent of American jobs (which require a diploma).

School completion has increased in recent years for students of color to an all-time high of 70 percent for black students, and 75 percent for Hispanic students, yet this still means that many students are not completing school. And this graduation rate still lags behind that of white students.

What this means is that black families are much more likely to live in poverty, and that they are at much greater risk for homelessness. In 2010, though black families made up only 12.1 percent of all families nationwide, they made up almost 40 percent of all families requiring the support of shelter systems.

And, because of the school-to-prison pipeline, black people are more likely to end up in the criminal justice system, which also increases their risk for homelessness, and intergenerational poverty.

Trauma and rethinking discipline

Schools and innovative educators are grappling with facts like these, and some are making progress. As it turns out, schools with high poverty and high minority student bodies can make a real difference for their students by fostering relationships between staff and students, and also acknowledging the role of trauma in their students’ lives.

The impact of trauma and toxic stress on student functioning has been gaining increased attention over the past few years. This has led to innovative practices in schools, and, even more recently, a lawsuit in California.

Students in Compton, Calif. have filed a lawsuit against Compton Unified School District stating that their schools punished rather than supported them for their trauma reactions to violence in their communities. This punishment was frequently suspensions and expulsions, rather than school-based protections and mental health supports.

This lawsuit highlights how race and socioeconomic status can also interact with trauma, presenting an additional challenge to students in high-poverty schools. When schools fail to think ecologically about the needs of their students, high levels of trauma and stress can thus become another obstacle for student success.

Conclusion

Children of color and children from poor backgrounds deserve equal opportunity, and an education comparable to their white or affluent peers. I think that we have become numb to the fact that people of color are more likely to be poor and at higher risk for homelessness. That there is a connection between these outcomes, the education system, racism of all types (implicit, explicit, institutional, historical), and generational poverty, should concern far more people than it does.

If we are okay with two school systems, why is that?

What You Can Do

- Interested in learning more about residential segregation? Read this article from The Atlantic on white flight.

- Test the degree to which you’ve internalized bias against different groups. The results may surprise you! Here is a link to an implicit association test from Harvard.

- Read this City Limits report on black families experiencing homelessness.

- Listen to this story from the public radio show “This American Life” about a school district that recently “accidentally launched a desegregation program” and the community outcry that resulted.

- Watch the HBO miniseries “Show Me a Hero,” about court-ordered desegregation and public housing in Yonkers, N.Y. in the late 1980s, and marvel at what hasn’t changed in the decades since.