Children across the state recently said goodbye to summer and headed back to school. Research shows that some of these students, through no fault of their own, will receive unequal treatment in the classroom. Perry Firth explains what that unequal treatment looks like and why it happens in this first part of her two-part back-to-school blog series. -Denise

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

As a graduate of the Seattle Public Schools system, and the student of so many wonderful teachers, I don’t like to think that being white made the education system a kinder, softer place for me.

But of course it did.

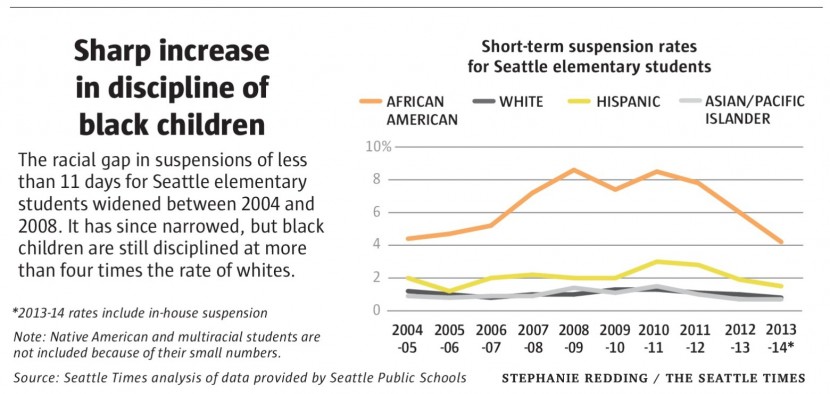

A Seattle Times report recently revealed that in the 2013-2014 school year, poor kids of color made up the bulk of the 69,754 suspensions and expulsions delivered across the state of Washington.

They were also more likely than white students to get in trouble for certain behaviors. For instance, in the 2013-14 school year, of those elementary students suspended for “interference with school authority,” 56 percent were black, while 6 percent were white.

The thing to understand is about this data is that black children do not suffer disproportionate punishment because they are “worse” than white students, but because they are more likely to be punished for behavior that white children get away with (we’ll get into the “why” of this a little later).

For instance, of all students classified as overtly aggressive in the 2010 study, black students were the most likely to be punished.

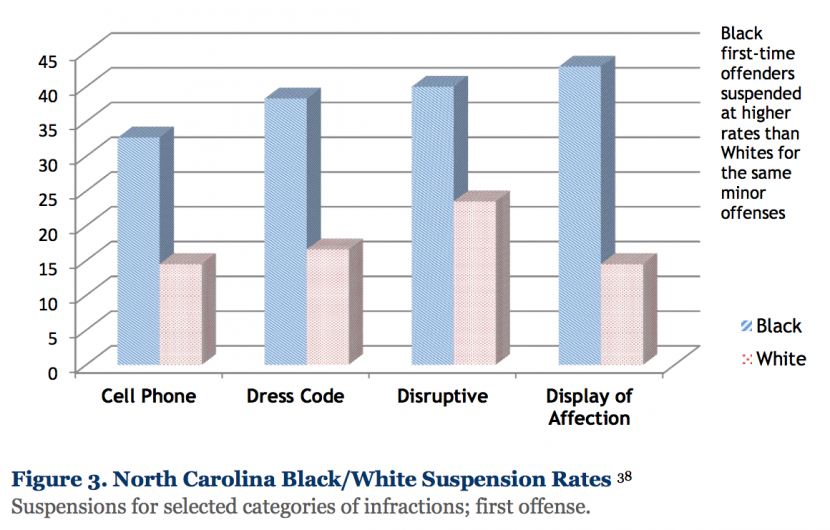

An example provided by the respected Kirwan Institute for the Study for Race and Ethnicity with Ohio State University highlights this: During the 2008-2009 school year in the state of North Carolina, black students were suspended at rates eight times higher than their white counterparts for cell phone use, and six times higher for dress code violations. For displays of affection they were suspended at 10 times the rate.

That is, they get punished much more severely and frequently than white students for the same behavior.

The disproportionality in discipline that black students face in Washington mirrors national data as well, and starts earlier than I suspected.

According to a recent NPR story, even though black children make up only 18 percent of preschoolers nationally, they account for about half of all out-of-school suspensions. Conversely, white children make up 43 percent of preschool enrollment and receive only 26 percent of out-of-school disciplinary sanctions.

This disproportionality continues as children grow older. According to the Civil Rights Data Collection Project through the Department of Education:

- “Black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students. On average, 5 percent of white students are suspended, compared to 16 percent of black students.”

- “While black students represent 16 percent of student enrollment, they represent 27 percent of students referred to law enforcement and 31 percent of students subjected to a school-related arrest. In comparison, white students represent 51 percent of enrollment, 41 percent of students referred to law enforcement, and 39 percent of those arrested.”

But are children of color just misbehaving more?

In the process of researching this piece, I read a recently published New York Times article that addressed disproportionality in discipline. It highlighted research like the fact that there are Southern school districts in which black children are suspended at rates “overwhelmingly higher” than white children.

Article commentators were skeptical that this was racist. A frequent comment or question was, essentially, “Yes but, black kids are probably acting out more. It is not racist if they just misbehave more.”

As I mentioned earlier, black children may be more likely to experience a harsher punishment than a white child for the same infraction. And, there is research highlighting that being black really does increase the likelihood for school suspension and expulsion, regardless of a child’s socioeconomic status.

This last point is important, because people frequently suggest that what really is happening with the disproportionality in discipline is a problem of socioeconomic status (i.e., it has nothing to do with racism). People who endorse this perspective suggest that black kids are more likely to live in poverty, and the barriers presented by poverty cause behavior problems, which are then present in black children and youth at relatively higher rates.

It is true that sustained poverty and stress can cause issues for children at school, which I’ve outlined in other blog posts. Low-income kids are more likely to run into school disciplinary procedures. However, researchers have addressed this argument as it relates to black youth and found that discipline is often because of race.

Here are some of their findings:

- Above and beyond poverty, race significantly predicts that black children will be over-represented among students who are suspended.

- Across all socio-demographic levels, black students are more likely to be suspended.

- Black students do not engage in more severe behavior than other students (which would warrant the use of procedures like suspensions).

- Schools with a higher percentage of black students are more likely to use zero-tolerance policies – or inflexible punishment regardless of extenuating circumstances — and aggressive disciplinary procedures than those with fewer black students. Schools with diverse faculty members are less likely to have a disproportionality problem, which is good news — except on average across the United States, 83 percent of teachers are white.

“The fact that race remains a significant predictor of discipline after controlling for a range of disciplinary infractions strongly suggests that factors related to student behavior are not sufficient to account for racial/ethnic disparities in discipline,” researchers at Ohio State University concluded.

However, what these facts leave unanswered is why this disparity happens.

Getting at answers

To help answer the question as to why students of color, and black and Hispanic students in particular, are more likely to be suspended or expelled, researchers at Stanford University designed two experiments with the purpose of generating insight into the racial discipline gap.

What they found is that a student’s race influences how their teacher interprets their behavior.

The researchers were able to determine this by giving actual teachers two different versions of student records of misbehavior. These two different records were exactly the same except for one thing: the names on the records. In some cases, the name was a stereotypically black name, in others a stereotypically white name.

- The first experiment asked teachers to rate the behavior contained in the case files along dimensions of severity, how annoyed it would make them, their thoughts on what an appropriate punishment would be, and whether they thought the student was a problem in the classroom.

- In the second experiment, teachers were asked if they saw a pattern in the behavior, and if suspension would be appropriate.

What both experiments revealed is that teacher perception of child behavior was influenced after they reviewed the second infraction (so not for the first one), and that racial stereotypes explained this relationship.

Essentially, teachers were more concerned about the student’s second instance of misbehavior if he/she were black than white. They also were more likely to recommend a harsh disciplinary sentence, including suspension, for the student with a black-sounding name.

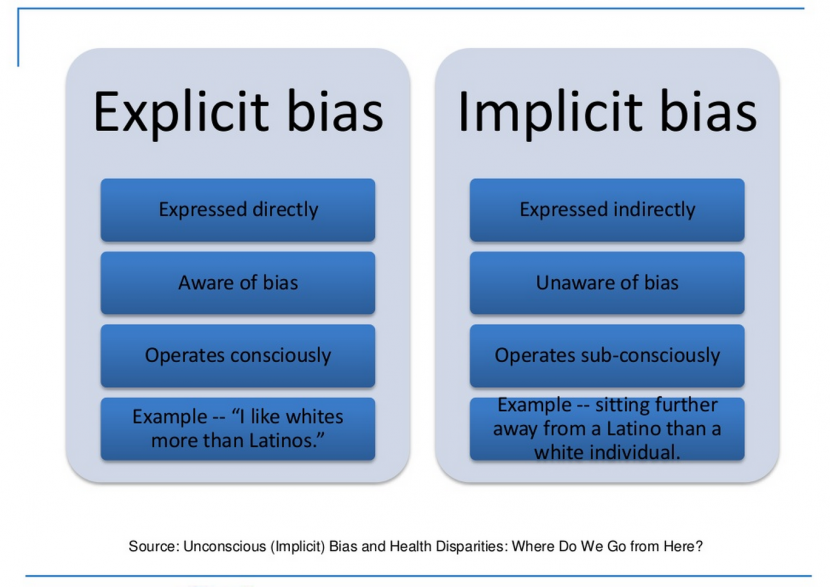

The teachers differed in their perceptions of student behavior because of stereotypes about black students as problems, a view that these teachers may not even know they had. Which brings me to implicit bias, and the role that stereotypes and unconscious thought processes play in shaping how we view people and behavior.

Implicit bias: The hidden racism

Recently, teacher training programs are paying more attention to how the background of their teachers influences how they perceive their students. After all, white middle-class students are no longer ubiquitous in they way that they once were, meaning that there is plenty of room for cultural clashes and misunderstandings. But more than misunderstandings, as the research above reveals, internalized stereotypes can influence how people see things. This internalization is called “implicit bias.”

Implicit bias is bias that operates outside of conscious awareness. According to the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University, it is “attitudes and that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. These biases, which encompass both favorable and unfavorable assessments, are activated involuntarily and without an individual’s awareness or intentional control…These associations develop over the course of a lifetime beginning at a very early age through exposure to direct and indirect messages. In addition to early life experiences, the media and news programming are often-cited origins of implicit associations.”

Importantly, people who hold egalitarian beliefs and who are not explicitly prejudiced against a specific group of people may still hold implicitly prejudiced beliefs. That is, you can believe in equality, yet still unintentionally engage in behaviors which would indicate otherwise.

It’s the kind of bias that is easy to minimize or deny. It can result in microaggressions — like when a person of color is thought to be a service worker, or a black man has a tough time getting a cab, but a white man is easily picked up. Or, when a woman or person of color is asked to speak for the entirety of their race or gender.

According to Psychology Today,

Microaggressions are the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership. In many cases, these hidden messages may invalidate the group identity or experiential reality of target persons, demean them on a personal or group level, communicate they are lesser human beings, suggest they do not belong with the majority group, threaten and intimidate, or relegate them to inferior status and treatment.

Thus, microaggressions can range from the relatively subtle to the more overt.

Further, in case I didn’t make this clear, implicit bias is not just about racism, but impacts all marginalized groups in our society. Implicit bias and stereotypes around class exist as well, such that people may believe the poor are lazy, or poor parents don’t care about their child’s education.

Implicit racism and microaggressions are common experiences for minority groups across our country, and the education system is no different. The presence of implicit racism (and even, I am sure, explicit racism) causes black and Hispanic children to be expelled at rates higher than white students.

However, what makes this reality troubling is not just that it happens, but that it can dramatically increase the likelihood that a child will drop out of school, fail to graduate, and end up in the prison system.

This relationship, between implicit racism, suspension, expulsion, and the prison system has been enshrined in the now infamous “school-to-prison pipeline,” an eerily accurate phrase for the intimacy that exists between school discipline and a jail cell.

In Part Two, coming out later this week, I’ll look at examples of the school-to-prison pipeline, troubling statistics on the re-segregation of American schools, the benefits of integration and how some schools are re-thinking discipline through the lens of trauma.

Pingback: Ms. Babbs()