Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

“The bodies are face down in the water. You can’t help the bodies.” The crisis responder is speaking into her phone, paraphrasing what she just heard from a veteran in crisis on the other end of the call.

Fast forward to another phone worker, and it becomes clear that she is listening in on a conversation between a veteran and his mother. The mother had called the crisis line when she realized her son had gone off into the Arizona desert to die.

It is Christmas Eve.

His mother pleads with him, tells him it would be a Christmas present if he came home.

Phones keep ringing at the suicide hotline, with responders doing everything they can to connect the voices on the other end of the line to resources. And to just connect.

One man calls the crisis line as an overdose of pain killers and alcohol starts to take effect. The crisis responder struggles to understand him, tells him to stay on the line. Even as the responder tries to direct police to his location, the caller’s lack of stable housing wastes precious minutes, as his speech slurs and his body’s response to his suicide attempt deepens. He must move to a place where the police can find him in the campground where he is staying.

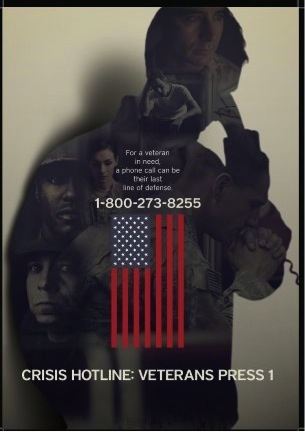

Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1: A timely documentary

All of this is captured in Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1, a documentary short produced and directed by Ellen Goosenberg Kent and produced by Dana Perry. A recent winner of the Academy Award for best documentary short, the film chronicles the efforts of crisis responders on the Veterans Crisis Line in Canandaigua, NY. The crisis line is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and its responders handle 22,000 calls every month from veterans dealing with trauma and the challenges of readjusting to civilian life. Many of the callers are suicidal.

The documentary is only 40 minutes long, and the cinematography is simple: crisis responders are filmed as they talk to different callers. We, the viewers, never hear the callers’ voices, to protect their privacy.

Therefore, everything viewers learn is through the responses of the responders to callers. Yet despite this removal from the actual person in crisis, this is a surprisingly effective way to illuminate the horrors of war, and the desperation of suicide.

However, this isn’t just a film about people who are suicidal—it is also a film about the responders who try to reach them.

All the responders profiled in the film are dedicated to the person on the other end of their call; it is clear from their body language and facial expressions that every caller gets their utmost attention. Watching that level of focus is watching passion in action.

Nonetheless, this type of work can take its toll; the responders discuss how there are certain calls that they still remember. This isn’t the kind of work that is easy to leave in the office.

However, their work is urgent: From about 1999 to 2011, roughly 27,000 veterans completed suicide. This means that more veterans have died than soldiers in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

And, on average, one veteran dies every 80 minutes, and their deaths account for 20 percent of all suicides in the United States.

The film also reveals something of combat-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): a soldier might leave the war, but that doesn’t mean the war has left him (or her).

That is the horror of PTSD.

It carries the worst of the war home with the vet — the scariest moments, the worst scenes, the feeling that more could have been done to help the soldier beside you. Guilt. Depression. Flashbacks. Increasing desperation followed by increasing isolation. Possibly substance use.

You could see how someone living with some combination of these symptoms would not only struggle with suicide, but without a strong family and safety net, be at risk for a variety of outcomes, homelessness included.

For instance, according to the American Psychological Association (APA), about 66 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans who are homeless have PTSD.

Where were the female callers?

As much as I enjoyed the film, I did have one question: Where were the female callers? Unless I missed something, all of the calls that made it into the film were male veterans. However, women now make up about 14.5 percent of the armed forces.

I know from past writing I’ve done for Firesteel that women in the American military have high rates of military sexual trauma, and related PTSD. Research indicates that 60 percent of women who experience sexual assault in the military develop PTSD, and that this form of trauma impacts anywhere from 22-45 percent of women in the military.

That is a lot of traumatized women.

So why weren’t they represented in the documentary? I am not critical so much as curious. For instance, did the filmmakers fail to find calls with female veterans that worked for the documentary? Was their intent to profile only the experiences of male veterans? How different would the documentary be if it had been composed entirely of female callers?

My own experiences as a crisis hotline responder

Watching this documentary really hit home for me.

I used to be a crisis responder at a local crisis line, doing the same sort of work profiled in “Veterans Press 1.” It was strange to watch people doing work I used to do, saying things I used to say.

It also brought back memories of the many people I have spoken to who were contemplating taking their own lives.

Here is some of what I learned from those I spoke to:

Being suicidal can be like falling toward the bottom of a deep dark hole. Except that when you think you’ve landed, the bottom shifts out from beneath you. From up above, you see the faces of the people who love you, looking down, hands waving.

If loved ones know you are suicidal, they tell you to try, to keep fighting. But you think to yourself, what do they really know about this kind of darkness?

But without these people, these people telling you that you’re loved, that you need to struggle for one more day, hour, or minute, that they would miss you and it’s worth continuing—without them the risk of completing suicide increases.

After resolving a call with suicidal callers, the ones I worried about were the ones who said they didn’t have friends or family.

Which brings me back to homelessness. By definition, homelessness represents a failure of social and family safety nets. If you have an affluent, loving, stable family, or affluent, stable friends, you are much more likely to be taken in long enough to get on your feet.

While friends can be made on the street, homelessness is nonetheless inherently isolating. Or to put it this way, we have all walked past a person who is homeless and clearly suffering, and done absolutely nothing. And they know it.

Subsequently, because of weak social and family ties, and the dehumanization that comes from life on the streets, the person experiencing homelessness is far less likely to see those “hands waving” as they contemplate taking their own life.

Homelessness and suicide

People experiencing homelessness in general have much higher rates of suicide than average.

Researchers interviewed a representative sample of 330 people experiencing homelessness. Ages of those interviewed ranged from 18 to 80, and interviewees were about 75 percent male. The researchers were interested in figuring out suicide ideation (thinking about it) and rates of attempt.

Here are some of their findings:

- 61 percent of those they talked to reported thinking about suicide

- 34 percent had actually attempted suicide in their lifetimes

- More homeless women than homeless men reported thinking about suicide (78.4 percent vs. 56.3 percent)

- More of the women reported attempting suicide than the men (56.8 percent vs. 27.6 percent)

- Being homeless for longer than six months was associated with increased suicidality.

Like the veterans calling the crisis line, the participants in the study were fighting a war, one that is often private, isolating, and misunderstood. With 41,149 Americans lost to suicide in 2013 alone, it is a battle that cuts across socio-economic status.

And yet.

If it is access to mental health care that can help someone, quite literally, find the will to live, then those living in poverty and homelessness are at a disadvantage.

In that case, suicide completion is more likely to occur. Moreover, as reported in an article in Time, people with a family income under $10,000 are 50 percent more likely to commit suicide.

Watching this documentary made me feel both hopeful and sad. Sad because there is so much suffering in the world and because I know that for every person who gets the help they need, there are others who don’t.

Yet there are people who devote significant parts of themselves to help others when it matters most. Because I know how effective this can be, I am also hopeful.

That two anonymous people can connect in one crucial moment, that a voice over the phone can help someone make the choice to live, is remarkable.

What you can do

- Spend some time learning about the signs that someone is suicidal on this WebMD page.

- Watch the Veterans Press 1 documentary, available for download on iTunes and Amazon Prime.

- Volunteer with a local charity that serves people experiencing homelessness. A little connection goes a long way in relieving suffering.

- In case you, or someone you know is in crisis, remember that you can call the Crisis Line of King County at 206-461-322 any time, night or day, 365 days a year. Someone will pick up the phone for you. The phone workers will listen and provide support, and generate resources for mental health care if needed.

- Another option is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (also the number that connects to the Veterans Crisis Hotline). Responders can connect callers to a crisis line in their area 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Pingback: Alla Forster()