Part Six in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

Throughout this series I’ve talked about the problem — of homelessness and poverty, their effects in the classroom, and the disheartening way toxic stress can interfere with a child’s ability to grow into a successful adult. With a specific focus on the relationship between the special education system and homelessness, I’ve also talked about the complexities of diagnosis — how homelessness can make it hard to see where “economic and environmental factors” end and disability begins.

Finally, I specifically focused on how well children receiving special education services for emotional disturbance do in school, using this category of special education as a way to illustrate how a child’s background can lead to specific special education placements.

Now that we have a framework, it’s time to talk about the policies designed to improve the educational success of children who are homeless and living in poverty, and the things schools can do to ensure that all of their learners thrive.

lesson plans in order. Now is a good time to also think about how best to serve youth who are

homeless — especially for school psychologists, charged with evaluating students for special

education. Image from pixabay.com

Therefore, Part Six in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system provides an overview of the policies that impact the day-to-day lives of children who are homeless and who also have disabilities. It also includes a brief overview of specific strategies that school professionals can employ when trying to serve their learners who are homeless with disabilities.

Legislation overview: McKinney-Vento and IDEA

There are two pieces of federal legislation that together work to ensure that children who are homeless and also have a disability receive special education services: the McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Because of these two pieces of federal legislation, students who are homeless and who also have disabilities are entitled to services that ensure equal access to the public education system. Together, they also provide for a range of services that allow these children to succeed — like transportation to and from school (via McKinney-Vento) and individualized education programs, or IEPs (via IDEA). And there is overlap between these two laws; children with disabilities should get transportation via IDEA.

Here is an overview of each one.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Act is a law designed to ensure that children experiencing homelessness still have equal access to the public education system.

Its mandates include:

- That barriers be removed which prevent children experiencing homelessness from entering the public education system.

- That children be allowed to continue their education in their school of origin, even if their family moves residences.

- That schools provide transportation to and from school for children whose parents are unable to take them.

- That students who are homeless be provided special education services when needed.

- That students who are homeless be provided Title I services (extra educational help) when needed.

- That students who are homeless can enroll in school without the documents required for stably housed children.

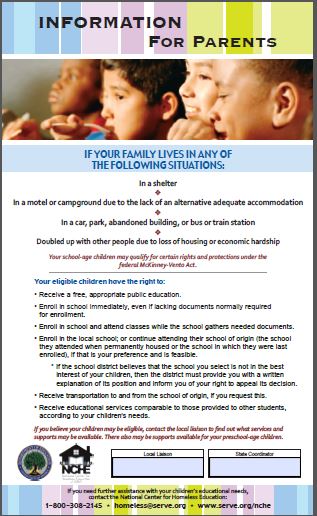

For a great overview on McKinney-Vento, check out this “Helping Homeless Students” brochure below.

only details McKinney-Vento, but lists all the homeless liaisons in King County school districts.

IDEA, or the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, is federal legislation that directs schools to provide a free appropriate public education to students with disabilities. It also mandates and describes how schools should provide special education. This ranges from stating that children should receive services in the least restrictive environment where their needs can still be met, to outlining special education procedural protections that enable parents to advocate for the rights of their children.

These are arguably the two most important federal laws in the lives of children experiencing homelessness who also have disabilities.

Together, they influence the day-to-day operation of schools and school professionals who work with youth who have disabilities, and who are also homeless.

In the next section we’ll look at practical strategies for implementing these mandates. Some of them will derive from these two pieces of legislation, and others are best-practice recommendations from organizations that work with students experiencing homelessness.

How school professionals can improve special education access for children who are homeless

In Part Four of this series we outlined some of the reasons that children experiencing poverty can struggle to access the services they need. The reasons ranged from school mobility to the challenge of ruling out environmental and economic causes of a child’s issues in school, to the reality that parents living in poverty can struggle to advocate for their child’s needs.

In light of these barriers, here are some specific things schools can do to help these children access special education services, broken down into four sections: Identification, Pre-Referral Strategies, Streamlining the Process, and Special Education Evaluation Tips. Many of these are from the National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE) and National Association of State Directors of Special Education.

- Identification

Because children and families experiencing homelessness can be hard to identify, here are some suggestions for reaching them about special education services:

- Schools regularly send home school packets and information for parents. Certainly at the start of the school year, and then periodically throughout the year, school staff could consider sending home (with children) easy-to-follow explanations of McKinney-Vento and IDEA, and a description of child and parent rights to a free and appropriate public education. Here is a website with an example of a McKinney-Vento flier for parents from the organization School Resources for Homeless Families.

- Develop short and simple posters and business cards describing special education services and how these can help students struggling with a disability, and place these in shelters, food banks, community health clinics, laundromats and convenience stores. Or download and post the posters about McKinney-Vento rights from the National Center for Homeless Education.

- You could also put simple and easy-to-follow information on IDEA and McKinney-Vento in the student handbook.

- Hold events throughout the school year that are family-friendly, and use these as opportunities to screen for mental and physical health needs. Consider using bus tokens, and providing food and school supplies to increase attendance.

- Foster collaboration between school staff. Create an environment where the teachers know the school psychologist and school counselor, and are comfortable bringing them their concerns about children.

- Provide staff trainings on IDEA, McKinney-Vento, and homelessness. Children living with homelessness will receive better services if school staff understand the causes of homelessness, and how it impacts children. As part of this, include information of how homelessness can show up in the classroom. Finally, ensure that staff are trained around sensitive ways to broach the subject of homelessness with children and families. This can increase the identification of children who do need special education services because it can help eliminate the stigma that keeps families and children silent about their housing situation. Contact your school district homeless liaison for more information. (This is the person appointed by the school district to work with children and families experiencing homelessness, in accordance with the McKinney-Vento Act).

- Develop working relationships with case managers, shelter workers and other social service professionals who work with families experiencing homelessness. Then, invite them to trainings on the special education system designed for parents. This will enable them to develop an understanding of the system that they can take back to their work with families. This can help with identification because it empowers the case managers to advocate for their clients when they suspect a child may need special education services.

2. Pre-Referral Strategies

Regardless of whether a child is homeless, school staff can help struggling students in ways that do not involve special education services.

The following is excerpted from Supporting Homeless Students with Disabilities, a topic brief published by the National Center for Homeless Education.

Try:

- Behavior management plans.

- Priority seating in the classroom.

- Assigning a peer and/or adult mentor.

- Writing down homework assignments or instructions.

- Regular meetings with the school counselor.

- Extra help before or after school.

- Supplemental education services through Title I or similar programs.

- Extra time to complete assignments.

- Other services the special education team or teachers might suggest.

These strategies would be very helpful to any student, not just one experiencing homelessness. By special education law, schools must try strategies like these and document their effectiveness before initiating special education evaluation. If the child continues to struggle, however, and it has been determined this is not because of poor-quality instruction, it may be time to push for special education evaluation.

3. Streamlining the Process

The following bullets are from Homelessness and Students with Disabilities: Educational Rights and Challenges, produced by the National Association of State Directors of Special Education.

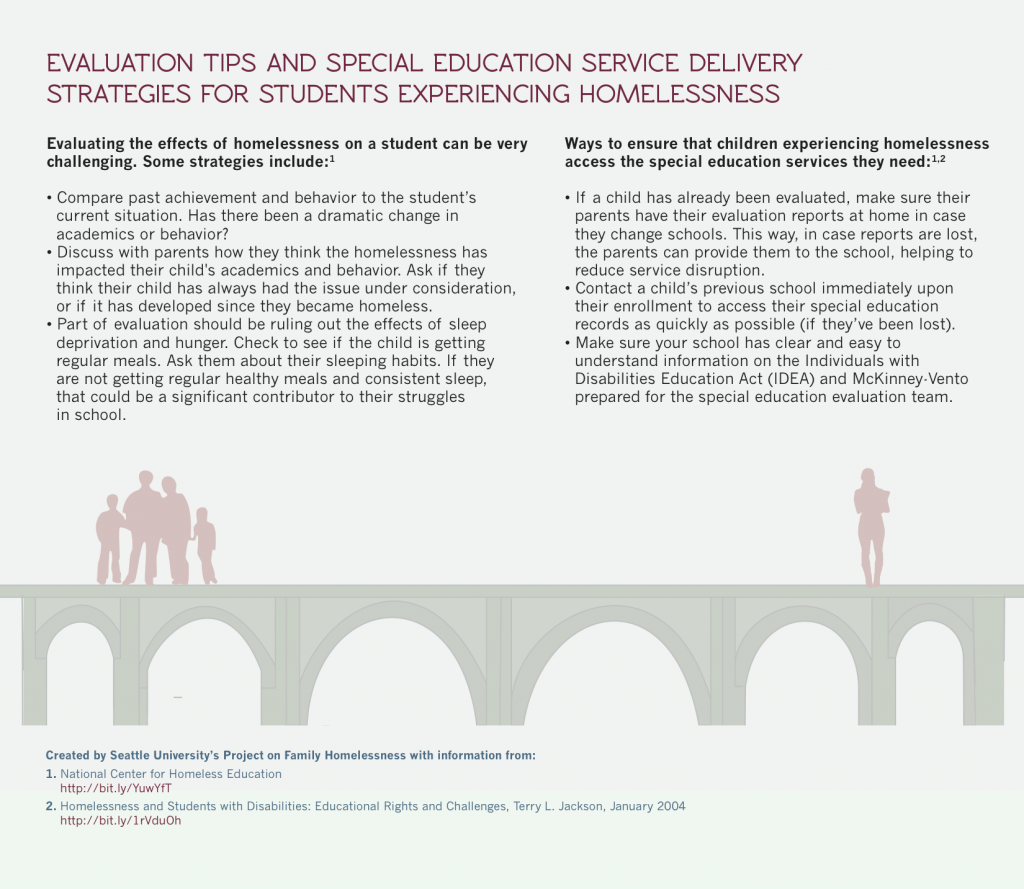

- If a child has already been evaluated, make sure their parents have their evaluation reports at home in case they change schools. This way, if reports are lost, the parents can provide them to the school, helping to reduce service disruption. That is, don’t provide the documents only when the student is leaving, but as soon as they are available.

- Contact a child’s previous school upon their enrollment immediately to access their special education records as quickly as possible. This reduces special education service disruption.

- Explicitly discuss with parents the importance of providing special education records to their child’s new school.

- If a student experiencing homelessness is in a new school, immediately implement their IEP, and then determine whether they need a re-evaluation.

4. Evaluation Tips

Given the barriers that children experiencing homelessness face in accessing special education, here are some strategies that may help these students access the services they need. Some of these are helpful when working with all learners, not just those experiencing homelessness; however, these all gain particular salience when evaluating un-housed students. Unless otherwise indicated/linked to, these strategies are from the National Center for Homeless Education. Note: Some of these are also required by law.

- Complete special education evaluations immediately if the child is known to be homeless. This can help address the problem of school mobility and unstable living situations as children move addresses. Also, prioritize the evaluations of highly mobile youth.

- For unaccompanied youth, appoint a surrogate parent to make special education decisions.

- Review all/any of the child’s evaluations, assessments, discipline referrals and teacher’s notes/observations from before the child became homeless. Then compare this information to any data that have emerged since the child became homeless to determine if the child is struggling because of the stresses of homelessness or because of a pre-existing issue. So basically, compare past achievement to current achievement.

- Talk with the child’s parents about their child’s past and current academic achievement. This will provide more information about how a child’s living situation is influencing their success in school, and further illuminate the cause of any academic or behavioral issues.

- Check to see if the child is getting regular meals. Ask them about their sleeping habits. If they are not getting regular healthy meals and consistent sleep, that could be a significant contributor to their struggles in school. Therefore, part of evaluation should be ruling out the effects of sleep deprivation and hunger.

- If you are worried about a child who is experiencing homelessness, and given the length of the evaluation and IEP process, start providing intervention and support services throughout the evaluation process, as opposed to post-diagnosis.

contributing factor to struggles in school. Photo from United Way of King County.

Note: While the evaluation team must rule out homelessness as the cause of a child’s struggle, homelessness and the behaviors associated with it are also not valid reasons for denying evaluations. For example, homelessness-linked behaviors like truancy and lateness cannot be used by the district to deny evaluation, even if it is assumed that those are the reasons a child is struggling. Rather, they are factors that are examined during the evaluation.

Difference between a 504 and an IEP and why it matters

I can see how frustrating it must be for social service professionals and child advocates to feel strongly that a child has a disability that is adversely impacting their academic performance, but find out that the evaluation team has determined they do not need an IEP.

However, as I noted earlier in this post, there are things schools can do that do not require an IEP (like tutoring and meeting with a mentor, for example).

Here’s another way to meet a child’s needs: through a 504 plan.

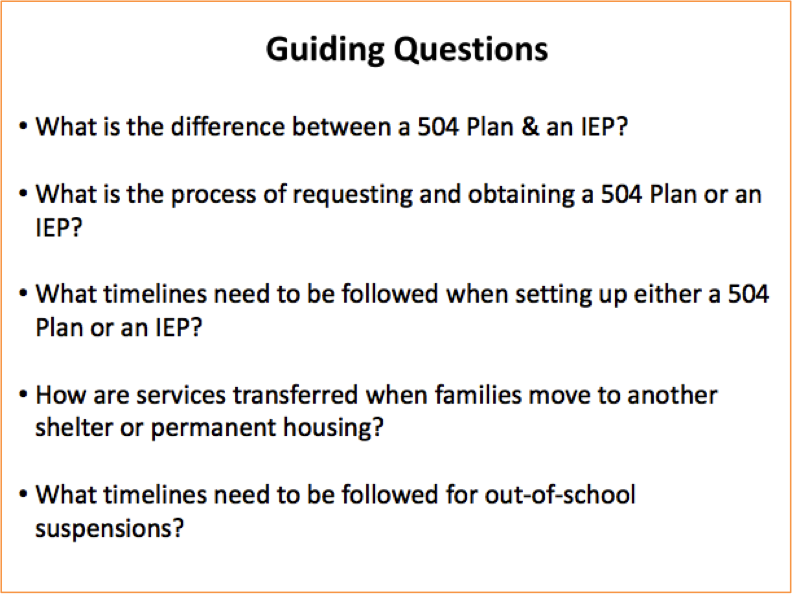

In June, I attended the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness Families with Children Committee meeting on special education. The presenter was Scott Raub, the Special Education Parent & Community Liaison from the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) for Washington state. Below are the questions that guided his presentation.

these questions are answered in this blog post, so refer to the presentation here for more

information.

His presentation was great because it outlined how parents and advocates can still get services for their child on a 504, even if they don’t qualify for an IEP.

This is especially helpful for children who are homeless. Because of the challenges around evaluating these students, and the requirements that must be met for a child to receive services under an IEP, a 504 may be the best route to ensure they get extra help. (At the same time, remember that you cannot “save a child” by saying they have a disability in order to receive extra services. Labeling, even for a 504, should be avoided unless the child truly does have a problem that needs 504 services).

Therefore, here is an overview of the difference between a 504 and an IEP, and how a 504 can help students who are homeless. This is pulled from Scott’s presentation and other sources.

Section 504:

- Unfunded civil rights law.

- Requires schools to remove barriers that prevent students from participating equally in school and associated activities.

- Designed to ensure that children with disabilities or health problems can still participate in school activities alongside their peers; prevents discrimination.

- A child doesn’t need to receive services under a specific disability category to qualify.

- It must be verified that their disability is causing substantial limitations to a major life activity.

- They get a 504 plan, as opposed to an IEP.

- They are served in general education.

- 504 plan: A child is eligible for a 504 plan if the school suspects that they have a disability, health problem, or other disorder. This does not need to be confirmed by a medical diagnosis. Anyone, including a child advocate, can initiate 504 proceedings. Similar to an IEP, a variety of sources are examined to determine if the child’s suspected disability/health problem is preventing them from fully participating in school, and is adversely impacting their academic functioning. If this is found to be the case, they get a 504 plan. The 504 outlines necessary accommodations, and is periodically re-evaluated. It requires the school district to provide accommodations or related services that a student needs to participate in any school program.

IDEA:

- Gives rise to the IEP.

- Child must be found to have a disability that requires specially designed instruction to be successful. This is different from a child who is receiving services on a 504 plan. It has been determined that children receiving services on a 504 do not need specially designed instruction to be successful, but do need accommodations to fully participate in school life.

- Is funded by the federal government.

- Child is placed within a specific disability category if it is found they have a disability.

for student eligibility for a 504 plan.

You could see the benefits provided to children experiencing homelessness by Section 504. Given the relationship between poverty, hunger, sleep deprivation and substandard housing in causing problems for children, section 504 could be wielded to ensure children in need of extra services receive them.

Further, as recorded by the National Center for Learning Disabilities, a student is eligible for a 504 plan and its protections even if they are simply “regarded” as having an impairment. And, because this is a civil rights law designed to remove barriers that impede access to public education, it works in the favor of children who are homeless living with somewhat “opaque” issues.

Cumulatively, it may be easier to get a child who is homeless on a 504 plan as opposed to an IEP. A specific plan for what they need to be successful is still developed (outlining classroom accommodations like seating plans), yet the process is not subjected to the more stringent requirements of an IEP evaluation. Basically, if it looks like a child won’t be eligible for an IEP, you can try a 504.

What I just outlined is brief and simplified, but I hope it provides a foundation for those readers interested in how to best serve this population of learners.

And remember, children who are homeless and have disabilities can still be successful. While there are barriers to their educational attainment, there are also teachers and other staff passionately committed to their well-being. Combined with broad policies and strategies designed to improve how the special education system serves these children, these school staff can and do make a difference.

What you can do

- Do you have examples of easy-to-understand handouts and other materials that describe IDEA, special education and McKinney-Vento to parents? Contact me at firthp@seattleu.edu, or submit a comment below.

- The National Center for Homeless Education is a great resource. I drew much of my research and tips from their work. If you are interested in learning more about what you read in this series, visit their website.

- Spend some time reviewing this “quick reference” guide for teaching students who are homeless developed by School Resources for Homeless Families.

Read other posts in this series

- Part One | Hungry, Scared, Tired and Sick: How Homelessness Hurts Children

- Part Two | Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Four | More Barriers to Learning: Homelessness and the Special Education System

- Part Five | A Web of Risk: Homelessness and the Special Education Category “Emotional Disturbance”

- Part Seven | Innovating Toward Academic Success: Empowering Students Who Are Homeless or Living With Toxic Stress

Pingback: New Infographics on Childhood Homelessness, Education, and Child Development | Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness()