Part Four in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

More than just an education, schools can provide a valued sense of security and safety for parents and their children. With the exception of the family unit itself, schools are arguably the most important institution in a child’s life.

In turn, this centrality positions schools to do more than just educate students in essential academic skills. From providing meals to children experiencing homelessness and poverty, to diagnosing learning and behavior disorders, schools facilitate many different aspects of child development.

For this reason, and given the diversity of needs and backgrounds presented by their students, schools are often the first responders for students presenting with unique and challenging issues. For example, school staff are often the first to recognize when a student is homeless.

In their effort to serve these learners, schools have evolved the special education system.

In this post we’ll examine an overlooked issue: The barriers that children experiencing homelessness face in accessing the special education system.

A brief overview of the special education system

Designed to provide a free and appropriate public education for all students with disabilities, the special education system comprises a complex array of referral and evaluation procedures, educational programs, laws and mandates.

Children are referred to the special education system for evaluation by a teacher, parent or other school professional when they have become concerned about suspected emotional-behavioral, learning, or other disability that is negatively impacting the child’s academic performance.

If the decision is made to go forward with testing and the child is found to have a disability that hurts their academic performance, the school creates an Individualized Education Program (IEP). This IEP outlines the specific things the child needs to succeed in school, as well as the goals for the child’s academic growth.

Special education categories

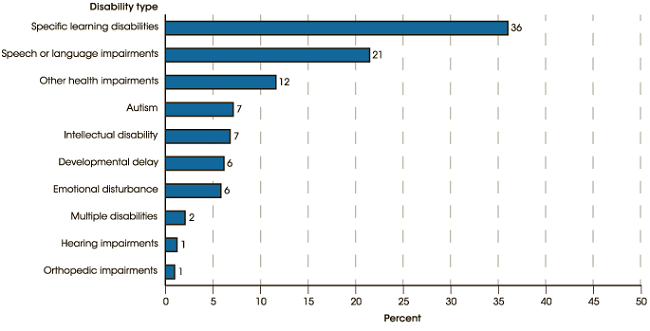

There are 13 disability categories recognized by the public education system and defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. They range from Specific Learning Disability, to Emotional Disturbance, which we’ll cover in Part Five of this blog series.

For a child to receive services under an Individualized Education Program (IEP), not only must they be found to have one of these disabilities, but the disability must also be found to have an adverse impact on their educational performance. For example, if a child has a speech impediment, but it isn’t affecting them academically, they won’t get services.

These 13 categories cover a diversity of children, whose disabilities emerge out of a range of causal factors, from genetics to trauma. And, one might add, the complicated neurobiological effects of homelessness and poverty.

(Later in this post we’ll talk about how homelessness and poverty can “masquerade” as a disability, and the importance of ruling out environmental causes of a child’s issues before providing services.)

How homelessness and poverty relate to special education

Everything I just wrote can seem pretty dry. However, it’s important to discuss the special education system in the context of children experiencing poverty, because they are more likely to end up receiving services in specific categories, like Emotional Disturbance.

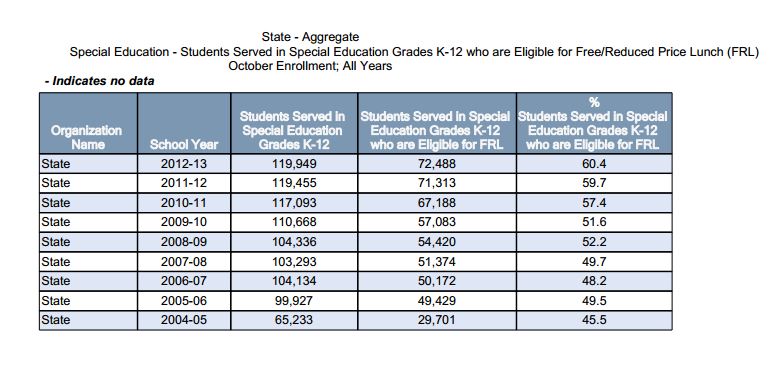

This is something we see locally, too. In Washington state, of nearly 120,000 students served in the special education system in grades K-12 in the 2012-2013 school year, 60.4 percent were eligible for free and reduced lunch – a primary indicator of living in poverty or on the edge of it. See the chart below. (Source: Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction)

Finally, a major theme throughout this series has been that children living in poverty and homelessness struggle at higher rates than their peers with a variety of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral issues.

Finally, a major theme throughout this series has been that children living in poverty and homelessness struggle at higher rates than their peers with a variety of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral issues.

According to Melinda Dyer, the program supervisor for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth with the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, 6,250 students experiencing homelessness are receiving special education services in Washington state. (Special thanks to her for providing this information.)

However, research also indicates that many children experiencing homelessness don’t get the services they need.

And given the relationship between early intervention for disabilities and developmental delays, and successful academic growth, this lack of academic services is concerning.

School professionals face unique diagnostic issues when evaluating children who are homeless

Poverty and homelessness, above and beyond hurting children, can complicate the efforts of school professionals trying to provide special education services.

Research indicates both that children who are homeless and in poverty are more likely to need special education services, but that evaluating them for special education services can pose “significant challenges.”

Reasons for this include:

- child mobility and school records loss;

- the complex effects of homelessness on child behavior; and

- the requirement that schools must rule out environmental causes (e.g., poverty, homelessness) as the reason a child is struggling.

And given that the effects of homelessness on children in the classroom often mimic indicators of a disability, evaluators have their work cut out for them.

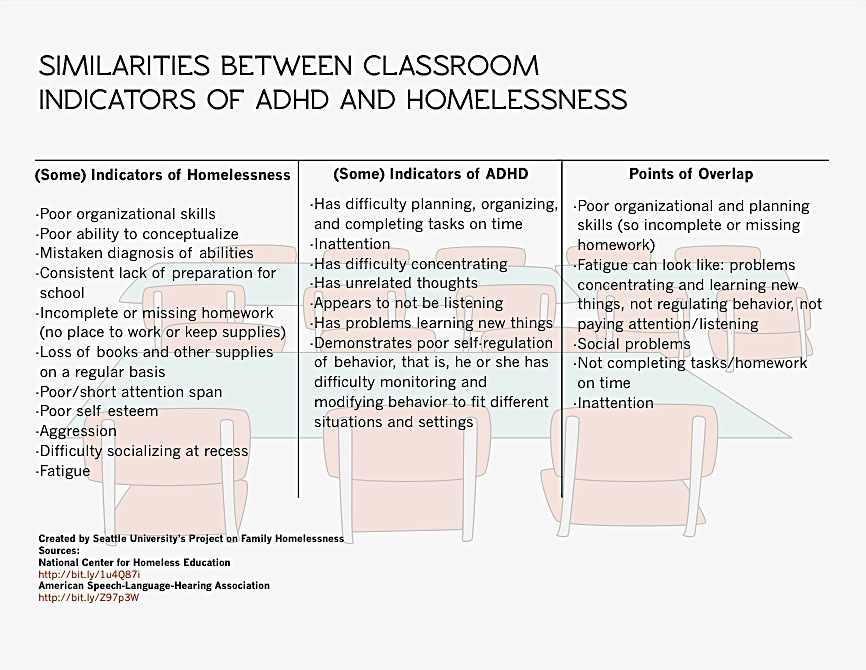

As an example, let’s break down some of the indicators of homelessness, and compare them to classroom indicators of Attention Deficit (Hyperactivity) Disorder (ADHD). ADHD is one of the most common childhood disorders, and one for which children can receive special education services if needed.

While the indicators of both homelessness and ADHD that I listed are only some of what an educator might observe, you can see how poverty and homelessness in the classroom can easily present as a host of disorders.

At the same time, children from impoverished backgrounds really do struggle at higher rates of a variety of issues because of the complex effects of stress and environment on brain development.

You could see how this may be confusing for evaluators. They’re mandated to rule out economic or environmental factors as the cause of a child’s struggles, yet they are confronted with behavior that looks very much like what one might see in a child with a disability: emotional-behavior problems, aggression, inattentiveness, skill deficiencies and slowed/poor achievement.

This makes differentiating the effects of homelessness from the effects of disability challenging.

Ultimately, this requirement that environmental causes be ruled out is appropriate. A child doesn’t have a disability just because their living conditions have prevented them from learning a skill. However, this can be frustrating for families and child advocates who want a child struggling with homelessness to receive intensive services.

In Part Six of this series, we will discuss the many actions that parents, educators, case managers and others can take to help children experiencing homelessness, other than requesting IEPs.

Barriers to accessing special education services by children experiencing homelessness

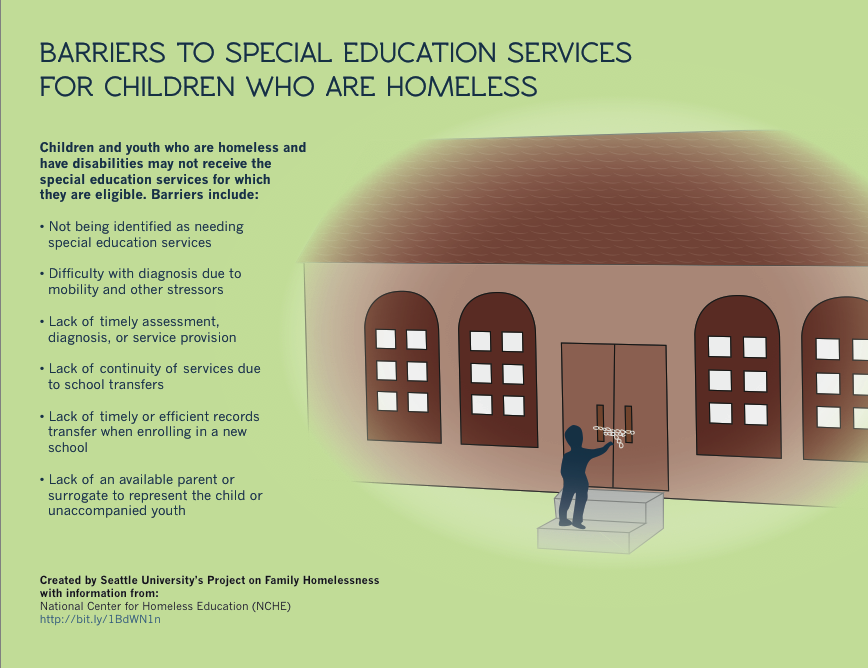

Children who are homeless face numerous barriers to accessing the special education system, even as they’ve been found to need services at two to three times the rate of children who are housed.

Specific barriers include:

- High rates of school mobility

- Disrupted education as schools are switched

- For some children, their determination to go un-noticed

- Problems with identification of disabilities by early childhood service providers, homeless shelter workers and homeless liaisons

- Discontinued services because of school transfers

- Slow assessment, diagnosis and service delivery

- Special education records loss. For example, a child receiving services at their old school could lose them if their records get lost in the move. If they don’t tell anyone they were receiving special services, they may not be given the specially designed instruction for which they are eligible until the school notices there is something “wrong,” or until the records are accessed later.

- Lack of an available parent or surrogate to represent a child or unaccompanied youth throughout the special education process; or language barriers between the family and school.

- In Washington state, new analysis by Columbia Legal Services shows that more than 4,600 of our homeless students are unaccompanied by a parent or guardian.

- Immigrant families – who already have difficulties accessing homelessness services in King County – also have challenges accessing the special education system. (For more about problems in Seattle’s special ed system, see this Seattle Times article from Aug. 30.)

This is a long list of obstacles, and for me at least, begs the question — Are children who are homeless really getting the services they need?

Children experiencing homelessness can struggle to access special education

The answer to that question seems to be “no.”

For many of the reasons listed above, children who are homeless do not always receive the special education services for which they are eligible.

- For example, an older study examining special education services used by children staying in Los Angeles shelters found that only 23 percent of those children who had disabilities had received evaluation testing or services, and that 45 percent of children who needed an evaluation were not getting it.

- And, at least as of 2000, 50 percent of states were reporting to the Department of Education that children who were homeless were experiencing “significant difficulties” accessing the special education services they were in need of.

- A report prepared by the Better Homes Fund (albeit in 1999), made a similar assertion, noting that children experiencing homelessness are less likely to receive special services, even though they need them more.

- According to the Better Homes Fund, 75 percent of housed children who need special education services receive them, compared to 38 percent of children who are homeless.

We need new data

Doing research on this question of access to special education services, I was growing frustrated with the limited amount of studies on this topic, as well as their age. You can always tell how “important” a topic is based on the amount of research you find on it; and an underserved population is less likely to have a voice.

However, a report published in 2013 from the Institute on Children, Poverty & Homelessness asserts that this lack of services persists. Mirroring my own observation, they also note that the research in this area is outdated.

Less able to advocate for themselves because of the very nature of their economic condition, and the invisibility it can create, many students are not getting the services they need.

Greater need does not always equal greater access to help. This is one of the sad and frustrating realities of the world we live in. Despite the efforts of committed educators and other professionals, children raised in poverty can become entrenched in inequality.

In writing this series, I have sometimes felt that for every child whom the system has “saved,” there is another it has failed. However, the feeling doesn’t linger when I think about how with every new school year, children and schools are given the opportunity to start over.

In the next part of this series we’ll talk about how students who have been diagnosed with emotional-behavioral disorders fare, both in the public education system and in life.

What you can do

- To learn more about how homelessness and poverty impacts children, spend some time perusing the amazing resources on the Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness site.

- Read more about the special education process here: Project IDEAL.

- There is a shortage of special education teachers. If you have an interest in teaching, consider channeling your efforts in that direction. Here’s a good source about the field.

- Subscribe to the Firesteel blog to learn more about the many issues associated with poverty and homelessness.

Read other posts in this series

- Part One | Hungry, Scared, Tired and Sick: How Homelessness Hurts Children

- Part Two | Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Five | A Web of Risk: Homelessness and the Special Education Category “Emotional Disturbance”

- Part Six | McKinney-Vento, IDEA and You: Strategies for Helping Homeless Children With Disabilities

- Part Seven | Innovating Toward Academic Success: Empowering Students Who Are Homeless or Living With Toxic Stress

Pingback: New Infographics on Childhood Homelessness, Education, and Child Development | Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness()