Part One in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

We had to wake up at 5 o’clock in the morning because our school was far away. Sometimes we had to go to school late, because we had to wait for the bathroom. But since it wasn’t our house, they could use the bathroom first. But at school, we would get truant. I could not go to recess because of this. — Quote from 12-year-old girl experiencing homelessness, in The State of America’s Children 2014 from Children’s Defense Fund.

Impoverished children are climbing mountains before they can walk. From lack of housing to hunger and violence, poverty places adult demands on child-sized shoulders.

Stability is crucial to the health and well being of a child. But in this post, Part One of our series on homelessness in the classroom, we’ll see how poverty and homelessness create an unstable world for children.

The bad news is that this instability can have lasting consequences for children. The good news is that there are many committed adults working to improving the lives of these children. However, before we get to solutions (coming at the end of this series), let’s talk about the many ways in which poverty hurts children. Understanding the problem creates a framework for answers.

Housing isn’t always safe shelter

Homelessness for families doesn’t always mean sleeping outside without shelter. In fact, the federal McKinney-Vento definition of homelessness for families includes those families “doubling up.” During the 2011-2012 school year, 75 percent of American homeless children and their families found shelter living with friends and family.

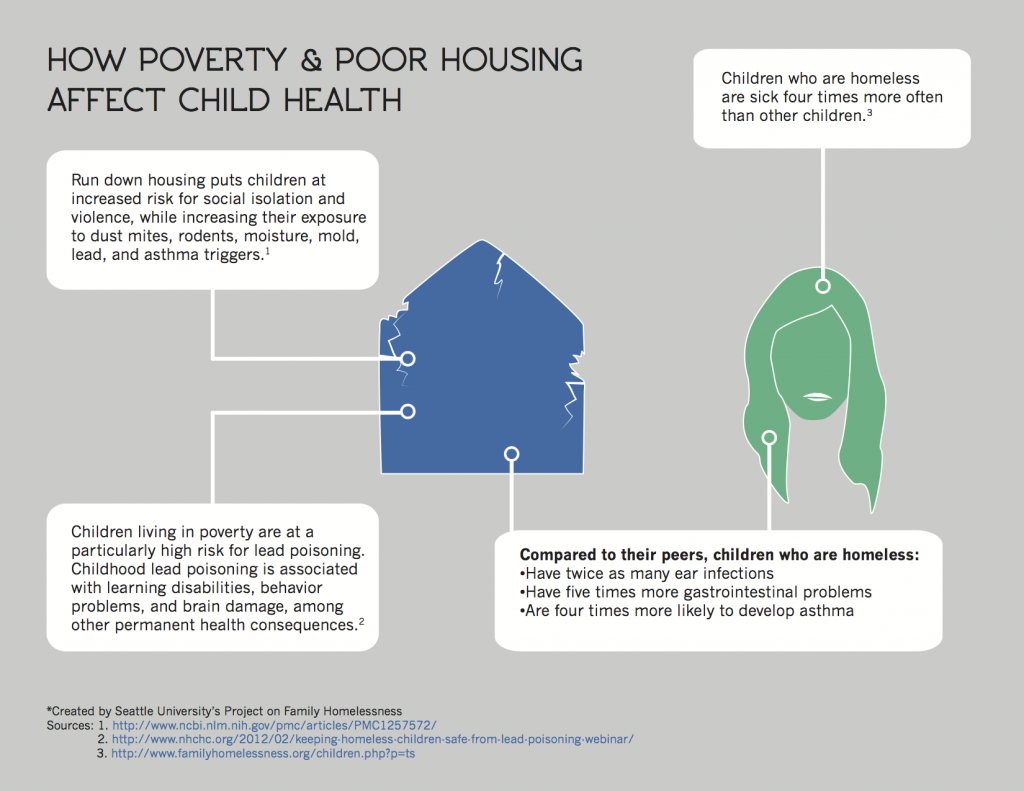

However, they may find themselves in dilapidated housing that poses significant health risks.

From the story of the girl at the beginning of this post:

We laid on blankets. It felt hard. There were little roaches that walked over us at night.

One little one got in my ear, and it was hard to take it out. It was nasty, because I could hear it scratching. It hurt a lot when I was trying to sleep. . .

Rife with lead, mold and infestations, housing for impoverished families can lead to significant health problems in children. Lead exposure especially is harmful to children, and if significant, can cause lead toxicity. This toxicity leads to permanent neurobiological changes, reduced IQ, and other health effects, according to groups like the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

For parents relieved to find housing, I would imagine that watching the roof over your head cause physical illness in your child is like watching a dream turn into a nightmare.

as America, there are children whose housing is making them sick. Photo from istockphoto.com.

Unfortunately, lack of or unhealthy housing is just one problem in what can be an ever-expanding web of risk factors for children living in poverty.

- Children who are homeless and poor also move 50 to 100 percent more than their middle-income peers. This movement contributes to frequent school changes, which is in turn associated with lower academic achievement.

- Poor and homeless children are less likely to eat nutrient-rich food while also going hungry; that doesn’t help their academic achievement either.

Says one young student interviewed by CBS’s 60 Minutes for their “Homeless Children: The Hard Times Generation” series, “It’s hard. You can’t sleep… And your stomach hurts, and you’re thinking ‘I can’t sleep. I’m going to try and sleep, I’m going to try and sleep,’ but you can’t ’cause your stomach’s hurting. And it’s cause it doesn’t have any food in it.”

Going to bed hungry, they are waking up sick.

Hungry and sick: Homeless children face health risk

Indeed, children who are homeless are sick four times more often than other children. Stressed, hungry, and tired, their young developing bodies are plagued with:

- respiratory infections (four times as high)

- ear infections (twice as many)

- gastrointestinal problems (five times more)

- and asthma (four times more likely)

at much higher rates than their peers, according to the National Center on Family Homelessness. Ultimately, these high rates of poor physical health can only make learning harder for students living with homelessness.

However, hunger, poor health, lack of housing (or unhealthy housing), mobility, and school changes are only some of the risk factors that children living in poverty contend with.

Like all children, their sense of safety is intimately linked to the strength and health of the adults around them.

Attentive maternal care is essential to a healthy child

There is nothing more central to a developing child’s mind and sense of security than his relationship with his primary caregiver. Chronically neglectful or inattentive care can harm a child’s ability to develop effective self-soothing skills. Conversely, strong parenting enables children to internalize these skills, preparing them to meet life’s challenges in healthy ways.

sense that the world is a secure, predictable place. Image from pixabay.com

The power of strong parenting is backed up by researchers who found that children living in an emergency shelter who received competent mothering started school with higher IQ scores and better self-control than children whose mothering was not as competent. In other words, attentive maternal care can buffer the impact of childhood stress.

Therefore, it’s troubling that:

- More than 60 percent of mothers experiencing homelessness have been abused, and that about half live with major depressive disorder. Mothers who are battling depression, the consequences of abuse and homelessness may be unable to provide the quality of care they could in better circumstances.

- Serious mental health problems in parents can lead to developmental problems in their children. Problems for parents can become problems for children.

So just as attentive maternal care can counteract stress, its absence, in combination with other risk factors, can create a void where stress overcomes a child’s delicate defenses.

Chronic stress harms children

Children are resilient. In a safe reliable relationship with a primary caregiver, there is much they can overcome. However, because of the very nature of the developing brain, and how it processes stress and trauma, most children living in chronic toxic stress will experience a detrimental change in how their brain works.

When children experience chronic stress, chaos and deprivation, the way their brain processes and responds to stress can be changed, or “dysregulated.” Basically, the child’s stress response system becomes very sensitive, and hard to turn off once activated.

This has serious consequences, such as conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, substance abuse and depression.

Diving beneath the skin and into the brain, we find that both the causes of homelessness (trauma, domestic violence and more), and homelessness itself, can change the brain.

This is why it is so essential for children and families experiencing homelessness and poverty to be given the resources, housing and supports they need early. Without them, children may end up living with the scars of their early experiences long after their situations have improved.

In Part Two of this series, “Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children,” we’ll talk about how the toxic chronic stress that frequently accompanies poverty and homelessness affects child development.

What you can do

- Read the next post in this series on how poverty and stress can impair children’s stress-response system and cognitive abilities.

- Download The State of America’s Children 2014 report from the Children’s Defense Fund.

- Listen to this StoryCorps interview between a mother and her daughter, who’s in high school, who are homeless and living in their car. Share it with others.

- Vote! Voting is an essential way to make our voices heard and make the world a better place for children. Organizations like the Washington Housing Alliance Action Fund track which politicians support legislation and funding for education and housing. If you haven’t registered to vote, you can do it here in time for the November 2014 general election.

Read other posts in this series

- Part Two | Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Four | More Barriers to Learning: Homelessness and the Special Education System

- Part Five | A Web of Risk: Homelessness and the Special Education Category “Emotional Disturbance”

- Part Six | McKinney-Vento, IDEA and You: Strategies for Helping Homeless Children With Disabilities

- Part Seven | Innovating Toward Academic Success: Empowering Students Who Are Homeless or Living With Toxic Stress

Pingback: New Infographics on Childhood Homelessness, Education, and Child Development | Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness()