Part Two in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

Even before a child is born, he or she is being shaped by the world outside of the womb.

Therefore, the effects of poverty can be seen from an early age. Children who are born to mothers who are homeless have low birth weight and require specialized care at four times the rate of their non-homeless peers.

This, combined with the environmental stress of poverty and ongoing physical and emotional needs, means that as early as nine months, poverty-related achievement gaps show up, only to widen as children age. This early inequality then sets the stage for intergenerational poverty.

Thus, deprivation during infancy and early childhood — when the brain is growing rapidly and aligning itself with the needs of its environment — can have powerful, negative, long-lasting effects.

Speaking at a meeting of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness in March 2013, Wendy Harris of the King County Developmental Disabilities Division Early Intervention Program shared this surprising fact: By the time a child is three years old, 85 percent of their brain has developed. That truly emphasizes the importance of healthy brain development.

Toxic stress hurts developing brains

In the previous post in this series, I talked about the impact of toxic stress. In the following definition is a clear and easy way to look at it:

There are many reasons that toxic stress, poverty and homelessness hurt children so much during these early years.

- One big reason is that all children must progress through crucial developmental stages, interactively exploring their environment as their abilities grow. This means that the brain, while always sensitive to experience, is especially sensitive from birth to five as young children advance through these stages in preparation for learning.

- It also means that if young children are raised in environments characterized by scarcity, neglect or abuse, their brains are not given the necessary resources to thrive.

Therefore, chronic intense stress during the sensitive developmental period of childhood can permanently alter how the brain responds to stress, holds memory and learns.

Stress can alter brain function

In extreme cases of toxic stress, the portions of the brain responsible for fear and impulsivity grow stronger, notes the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child in a paper published by Harvard University. At the same time, the areas of the brain responsible for behavioral control, planning and reasoning are weakening.

- This may explain why children raised in chronically stressful environments are more likely to have emotional-behavioral disorders, and why about half of children who are homeless end up developing anxiety or aggression.

- This also means that children raised in these types of environments are more likely to have problems planning and controlling their behaviors while also responding more intensely to neutral environmental events, remaining upset and anxious long after the event ends.

So, this is another reason why it’s important to provide housing and services to families with young children, to minimize the impact of toxic stress. It can also help explain why — even when a homeless child becomes stably housed — issues may still arise that are related to the effects of toxic stress earlier in life.

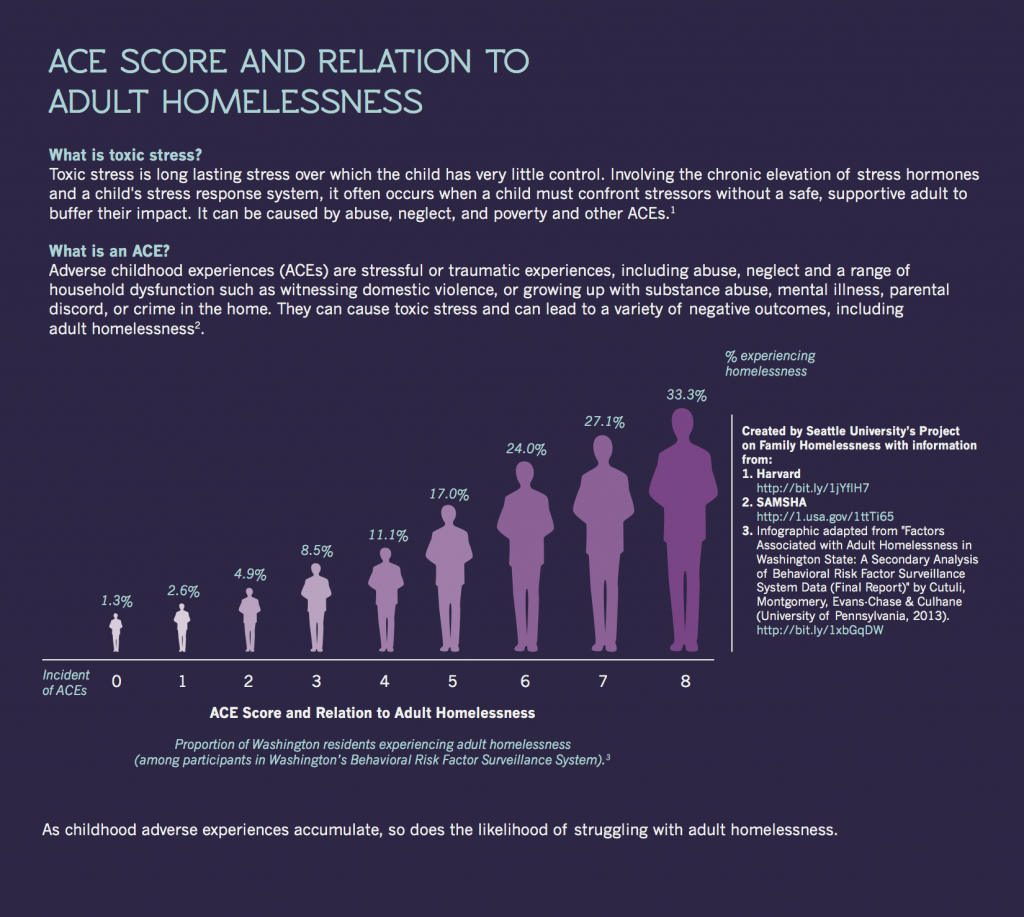

If the adverse experiences that prompted the toxic stress are not mitigated, they can accumulate, even leading to homelessness as an adult.

Toxic stress and Adverse Child Experiences

You may have heard of ACEs, or Adverse Child Experiences. ACEs are stressful or traumatic events in childhood which have been found to increase adult health risk for everything from cancer to early mortality.

Because of the potentially life-long ramifications of highly stressful and traumatic events, looking at how ACEs relate to adult well being is a helpful framework when we are discussing toxic stress in childhood. This is because the reason ACEs are harmful in the first place is because of the toxic stress they can cause in children.

Sadly, ACEs have even been found to predict risk of adult homelessness, as this infographic reveals.

Toxic stress can hurt a child’s ability to form relationships

Being raised in a toxically stressful environment can impact social information processing as well. For instance, research has revealed that children who have been raised in volatile environments may see hostility and threat in someone’s face when it isn’t there.

Children who have been traumatized, in particular, can become hyper-aware in this way, a result of highly sensitized fear and survival responses. While this is helpful in environments where threat to safety is a constant companion, it also means that their responses to neutral or non-threatening occurrences is outsized.

This, combined with seeing hostility in others when it isn’t there, can impact a child’s ability to form social relationships, trust others and handle their emotions appropriately. It may make these children seem as if their emotional outbursts come roaring out of nowhere. But really, given their brain’s appraisal of risk in their environment, these reactions are in line with their perception of danger.

Unfortunately, impaired social information processing is only one way that intense stress can harm children.

“Executive function”: Another victim of toxic stress

Stress hurts the developing brain in many core areas, but the prefrontal cortex — the outermost layer of the front part of the brain — is especially sensitive to stress and deprivation during childhood. This area of the brain is crucial to a group of important cognitive processes called “executive function.”

The prefrontal cortex enables humans to make and follow plans, focus attention, inhibit impulsive behaviors, hold information in mind and incorporate it into decision making. It also has a role in social relationships.

Cumulatively, these skills comprise “executive function,” and they are central to success both in school and in life.

In school, it is executive function which enables children to:

- solve problems, especially those which involve multiple-components (think multi-step word problems),

- remember to stay on top of long term assignments,

- problem solve, and

- handle rule adjustments.

Essentially, executive function helps children learn and use appropriate classroom behavior.

Therefore, it is no surprise that children who exhibit indicators of strong executive-function skills (like being able to pay attention and keep information in mind) make bigger gains on tests of math, language, and literacy during preschool than their peers with weaker executive function skills.

Unfortunately, executive function can be damaged in children who have experienced toxic chronic stress, whether the cause is neglect, abuse, or cumulative effects of poverty.

These children are less able to ignore irrelevant distractors in their environment, focus, and hold information in short-term memory. Given that these are the very things asked of them to succeed in school, it is no wonder that academic skill deficiencies start to emerge.

Thus, toxic stress, poverty, and homelessness start out as disadvantages, but become deep-seated inequality, as their effects start to widen the gap between where a child is academically, and where they need to be.

Summary

- Early brain development is affected by environmental conditions.

- Homelessness and poverty can have lasting consequences because they can create toxic stress.

- Toxic stress can alter how the brain and body respond to and process stress.

- Toxic stress can damage executive function, memory, learning and social information processing.

In the next post in this series, Part Three, coming Monday – “Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance” — we’ll talk more specifically about how poverty, homelessness and stress impact academic performance.

What you can do

- Spend some time perusing the information and resources at Harvard’s Center for the Developing Child. They do a great job of breaking down complex information on child development, with specific attention to how stress and poverty hurt children.

- Read Why Child Care Matters: Investing In Our Future Early On, written by guest blogger Sarah Swihart Miller for Firesteel. It provides great context for what was discussed in this post, but takes things a step further to discuss how homelessness hurts academic success. (Hint: This is a great primer for the next part of this series on how homelessness and poverty can affect academic success).

- Get acquainted with the fantastic resources available from Washington Alliance for Students Experiencing Homelessness (WASEH). Their data analysis of student homelessness in Washington state is something our project relies on regularly.

Read other posts in this series

- Part One | Hungry, Scared, Tired and Sick: How Homelessness Hurts Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Four | More Barriers to Learning: Homelessness and the Special Education System

- Part Five | A Web of Risk: Homelessness and the Special Education Category “Emotional Disturbance”

- Part Six | McKinney-Vento, IDEA and You: Strategies for Helping Homeless Children With Disabilities

- Part Seven | Innovating Toward Academic Success: Empowering Students Who Are Homeless or Living With Toxic Stress

Pingback: New Infographics on Childhood Homelessness, Education, and Child Development | Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness()

Pingback: Is Today the Day? | Seattle University's School of Theology & Ministry()

Pingback: Homelessness, Toxic Stress, and Children’s Brains | Melancholy Jaques()