Part Five in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

For some students, educational success is almost a given. They get good grades and attend college with an ease so natural it almost feels pre-ordained. There are many reasons why this is so, not the least of which is a stable middle-income family.

However, other students do quite poorly, struggling in school for years before they drop out.

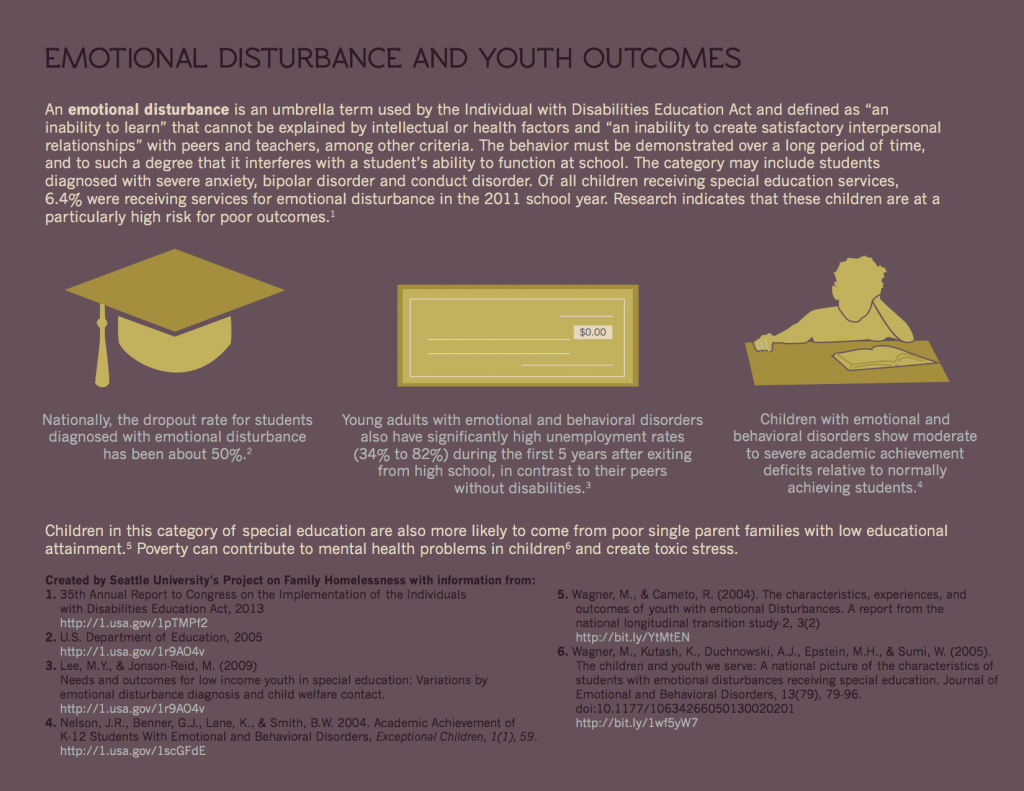

There is one group of students who have particularly poor outcomes, both in educational attainment, and other indicators of life “success”: Students diagnosed with emotional-behavioral disorders who receive services under the special education category Emotional Disturbance.

Making up six percent of the special education population, the children who have been diagnosed under this category provide an example of how poverty, other demographic variables, and educational practices all interact to influence not only school success, but special education placement. In Washington state, there are nearly 8,000 students receiving services under this category.

- In previous posts, we talked about how homelessness and poverty can cause children to struggle at higher rates with a variety of issues, and that one of these can be problems with emotion regulation. For example, children living with homelessness are more likely to have emotional-behavioral problems than their stably housed peers.

- I also talked about the fact that children who are homeless are more likely to need special education services, and that poverty also increases the risk a child may struggle in school.

As it turns out, there is a relationship between experiencing poverty and toxic stress (and trauma) in childhood, and the special education category Emotional Disturbance.

More specifically, many of the children receiving services under this category are from impoverished backgrounds. And at the same time, because of high dropout rates, many are unable to achieve the stability, education and employment they need to rise above their childhoods.

So when we look at how children fare after receiving services in this category of special education, we recognize some of the factors which can contribute to intergenerational poverty.

But before we begin, however, here is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) definition of emotional disturbance.

What is Emotional Disturbance?

The Emotional Disturbance category of special education is a condition exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree that adversely affects a child’s educational performance:

(a) An inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors.

(b) An inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers.

(c) Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances.

(d) A general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression.

(e) A tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems.

Poverty, Emotional Disturbance and dropout rates

Let’s look at some statistics related to emotional disturbance and success in school and life.

- Three percent of students who drop out of high school have emotional-behavioral disorders. And of course, this increases their likelihood of unemployment and poverty.

- Through 2011, the dropout rate for children in the Emotional Disturbance category of special education never fell below 37 percent.

- As of 2008, low-income students dropped out at four-and-a-half times the rate of their high-income peers. This too can contribute to intergenerational poverty, and even homelessness.

- Children diagnosed with emotional disturbance are more likely to come from families who live below the poverty level.

Looking at these figures, we see a cycle emerge. Children from poverty are more likely to have emotional-behavioral disabilities, and to end up receiving services under the category Emotional Disturbance. At the same time, children with emotional-behavioral problems are more likely to drop out than any other student population. Compounding this situation is that even if a child doesn’t have a diagnosable mental health issue, poverty means that they still face a high dropout rate compared to middle-income peers.

And, students who drop out of high school are going to struggle to find secure employment.

Other factors associated with Emotional Disturbance

The decks may be stacked against these children for other reasons, too.

- Research indicates that these students are disproportionately likely to come from households with multiple risk factors. For example, children from single-parent households with low educational attainment are much more likely to be placed in this category.

- Also, much as has been found with children who are homeless, the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2 revealed that nearly 38 percent of students in the Emotional Disturbance category have been retained (held back) one grade, and that compared to other students with disabilities, students who have emotional-behavioral disabilities move much more than children in other disability categories. As a group, these kids have attended five or more schools since kindergarten. This may be because poor families move more than those at a higher income level, and also because the child has caused problems in school, resulting in school reassignment by the school district.

In turn, these students have some of the worst outcomes of all students served in either special OR general education, despite the fact that they have no specific cognitive issues.

Indeed, research indicates that children living with emotional and behavioral problems demonstrate moderate to severe academic skill deficiencies, and that this starts early.

As young as second grade, children being served under this category of special education have been found to perform worse than their peers in vocabulary, listening comprehension, spelling, social studies and science.

Ultimately, because of the lack of academic skills, traumatic and impoverished backgrounds, their alienation from school, and the complexity of meeting their needs, they also are more likely to:

- Be involved in the delinquency system: According to the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2, 58 percent of students with emotional disturbance have been arrested at least once.

- Abuse substances: Frequently, this is an attempt at self-medicating their problems.

- Be unemployed post-graduation: Unemployment estimates for this group range from 34 to 82 percent. Research indicates that this is because of a lack of social and job skills. Even if hired, these young people have a high rate of being fired.

- Fail to attend college.

- Drop out of high school.

- Have unprotected sex, because of the impulsivity and low self-esteem associated with emotional-behavioral problems.

Further, for many of these students, their outcomes in life are influenced not only by poverty, but by race, gender and some interesting trends revealed by special education practices.

African-American boys are over-represented

The Emotional Disturbance category of special education is actually a hot-button issue in the field of special education. There are many reasons for this, including that these children don’t always succeed in the way that we would hope. However, a major reason it generates controversy is because of the fact that African-American boys are more likely to end up in this category than their white peers.

For example:

- Seventy-six percent of all students served under this category of special education are male.

- And, controversially, black boys have twice the rate of placement in this category than their white peers. Compared to the general population, black boys are disproportionately placed in this category of special education. Reasons for this include bias in referral and testing procedures, and according to some researchers, that black children are more likely to have been raised in poverty, increasing their risk for the outcomes discussed throughout this series.

- Once placed in the special education system, African-American boys are also twice as likely to be placed in a restrictive setting than their white counterparts – despite the fact that schools are supposed to place students in the least restrictive setting possible where they can be successful.

For example, at least as of 2002, the National Education Association was reporting that only 33 percent of black students with disabilities spent most of their day in general education – a less restrictive setting than a classroom where only students with special needs are served – compared to 55 percent of white students with disabilities.

All of this is concerning for several reasons.

- It shows how race can influence the behavioral interpretations made by school professionals, whether or not it is implicit bias or explicit racism.

- For all the good that special education does (and it can yield real, tangible benefits), an unfortunate reality of the system is that children who find themselves in it are frequently subjected to lower expectations. That means many of these boys are implicitly given the message that they are less capable.

- As any good teacher knows, students taught in an environment of low expectations rarely excel. Rather, they internalize that they are “stupid,” and meet the standards set for them.

I bring all this up to illustrate how child — and later adult — outcomes are influenced by risk factor after risk factor, by gender and race, by special education labeling, and even teacher expectations. This only scratches the surface.

Toxic stress at play again

Why the poor outcomes? For at least some of these students, it is the effect of toxic stress on brain development.

Many of the outcomes faced by these children occur through a confluence of events.

Starting young, children raised in poverty and homelessness are more likely to be exposed to high levels of toxic and chronic stress. In turn this impairs their brain’s ability to effectively process stress, impacting everything from the pre-frontal cortex to the amygdala and the hippocampus. This means that many of these students end up in the special education category Emotional Disturbance because of environmental effects, and neurobiological changes in the brain. Also, as discussed earlier, many of these students come from families with multiple risk factors known to impair child development.

Thus, many of the challenges facing these students involve weaknesses in the brain’s regulation of emotion and behavior, and less ability to refrain from impulsive acts. They also struggle socially. These are skills linked to the prefrontal cortex, and the social processing of information. They can also be a result of trauma. Children who have been maltreated may struggle in the school environment.

Poverty and disability creates web of risk

Finally, when considering how this interacts with gender and race, we see how many of these students end up getting caught in a web of risk.

However, what is maybe less apparent is how poverty can manifest in a specific category of special education. In doing research for this post, I was struck by how the children diagnosed with emotional-behavioral disabilities were more likely to come from single-parent families with low education, and that they traditionally have the highest dropout rate of any student population. For me, this resonates of intergenerational poverty, and how intense mental health needs and socio-demographic factors like race can interact to increase the likelihood a child will struggle.

Finally, the reality is that many students, both those with and without a diagnosis, don’t get the mental health care they need. Research indicates that students who do have a emotional-behavioral disorder, and who need special education, get diagnosed and receive help later than their peers with other disabilities.

This is because diagnosing emotional-behavioral disorders can be more challenging than other disorders, but in some districts it may also be because school psychologists often have very high case loads. Charged with evaluating children, they frequently have more students than they can quickly get to. For example, the National Association for School Psychologists recommends that there be a school psychologist-student ratio of 1:1,000; however, many school psychologists serve more students than that.

And even with an individualized education program and behavioral supports, the intensive therapy they need is often financially out of reach. Schools are rarely equipped to provide that level of care, and school psychologists and counselors often have more students than time.

Ultimately, the success of vulnerable learners rests not only with schools, but with communities. Early identification and intervention are essential, as are coordinated mental health and school systems.

Yet as a society we need to also invest in wrap-around services that stabilize families, and of course, safe, healthy, affordable housing.

No matter the strength of a child’s school or the quality of the school’s mental health services, students will never be at their best without a stable home and a stable family at the end of the school day.

What you can do

- Read the National Association for School Psychologist’s position statement on racial and ethnic disproportionality.

- If you are a school professional, consult your school psychologist first, if you have one. If not, get to know your community mental health providers. You could do this by contacting 211 and asking for referrals, or by looking up local agencies that serve youth, and then introducing yourself. If you establish a network of providers, it will be easier to refer struggling students to the help they need.

Read other posts in this series

- Part One | Hungry, Scared, Tired and Sick: How Homelessness Hurts Children

- Part Two | Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Four | More Barriers to Learning: Homelessness and the Special Education System

- Part Six | McKinney-Vento, IDEA and You: Strategies for Helping Homeless Children With Disabilities

- Part Seven | Innovating Toward Academic Success: Empowering Students Who Are Homeless or Living With Toxic Stress

Pingback: New Infographics on Childhood Homelessness, Education, and Child Development | Seattle University Project on Family Homelessness()