June is LGBT Pride Month. This year we have much to celebrate: The marriage equality movement has picked up tremendous momentum, and same-sex marriage is now legal in 20 states.

Though Americans’ attitudes toward the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community have become significantly more positive since Stonewall, there is still a lot of work to be done. As the organizer Janani Balasubramanian said in a recent interview, “The gravest violences queer and trans people face are not related to marriage. They’re related to healthcare, to housing, to police brutality and profiling, to prison, to detention, to employment, to poverty, to homelessness.”

At Firesteel, we are particularly interested in understanding and illuminating the struggles with poverty and homelessness that many members of the LGBTQ community experience. Thanks to Sarah, the insightful and delightful AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer on my Community Engagement team, for researching and writing today’s blog post. – Denise

Written by Sarah Bartlett, Community Engagement Coordinator for YWCA Seattle | King | Snohomish

“I was struggling to make ends meet,” Anna White says, adjusting her hat in the brightly lit dining room at Angeline’s Day Center for Women, the hard-working kitchen staff preparing lunch just behind her. “I applied for low-income housing, but it’s discouraging to hear about spending three to five years on a waiting list.”

Anna is one face among many at Angeline’s shelter — a woman, mother, and veteran struggling to understand her situation and find her way out of it at the same time. Anna ended up at Angeline’s after leaving an unhealthy living situation where she felt uncomfortable with her roommate. After living in a stable apartment just a few months ago, Anna now bounces between shelters, the streets, and family members’ homes.

Though Anna has a supportive family behind her, she feels trapped in the cycles that often perpetuate homelessness: lack of access to grief counseling and a history of incarceration. The situation is challenging enough, but her sexual orientation can also put her in a more vulnerable position. “I’ve experienced homophobia when I was just trying to get services,” she says, “and, on top of that, to be black and gay — that isn’t good.”

Lack of family and societal acceptance

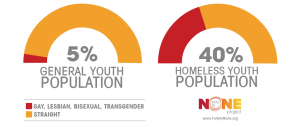

LGBTQ homelessness is not a new problem, and it begins early. As many as 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ, and oftentimes they end up trapped in a cycle of abuse, poverty, and street life that lasts well into adulthood.

Experts typically blame a lack of family and societal acceptance for the high incidence of homelessness in the LGBTQ community. The National Coalition for the Homeless reports that 58.7 percent of LGBTQ homeless youth have been sexually assaulted, compared to 33.4 percent of the heterosexual teen homeless population. The suicide rates for LGBTQ homeless youth are more than twice as high as for heterosexual homeless youth. Furthermore, queer youth are more likely to succeed in their suicide attempts than heterosexual youth.

Jody Waits calls the statistics “breathtaking.” Jody is the Director of Development and Communications at YouthCare, a Seattle-based nonprofit that provides services to homeless youth.

Jody points out that an LGBTQ identity can compound many of the issues homeless youth are already facing. All homeless youth are at high risk of mental illness, sexual trauma, violence, incarceration, and dropping out of school. It’s hard enough to access housing, education, and other basic needs when you are a homeless youth, “but for LGBTQ young people it’s 10 times harder than that,” she says. “Very often, LGBT teens have no concept that their life can be good.”

These challenges don’t fade when teens become homeless adults like Anna, and once on the streets, LGBTQ youth and adults face a whole new set of challenges.

Need for culturally appropriate services

Choosing to access new services as a homeless person can be a challenge for anybody, says Rochelle Calkins, Program Manager at Angeline’s Day Center for Women. But when an LGBTQ individual enters a new environment, “there’s always this thought of ‘am I gonna be OK here?’ A lack of culturally appropriate services can keep them homeless.”

Most homeless services are organized to serve straight, cisgender people, often specifying “only women” or “only men.” This traditional gender separation makes it challenging for LGBTQ individuals to access supportive, culturally competent services. For example, women’s shelters might be inundated with female clothing, but a female client who needs access to men’s clothing will have a hard time finding what she needs. Group showers and gender-segregated bathrooms or sleeping arrangements create further barriers for people who do not identify as cisgender.

There are exceptions. ISIS House, for example, is a transitional housing unit specifically for LGBTQ teens, run by YouthCare. At Angeline’s, staff treat transgender women as women, accepting anyone who presents herself as female. But that’s sometimes a gray area, Rochelle says, adding “who am I to dictate what presenting as a woman is?” She also believes that transgender men can be the most challenging clients to reach, as they face rejection from women’s and men’s shelters, as well as significantly increased risk of violence. Service providers agree that there simply aren’t enough culturally competent services for LGBTQ people, and those that exist face funding problems.

Rochelle, Jody, and Anna feel positively about progress made in the past several years, referencing marriage equality, greater presence of openly gay celebrities, and the repeal of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy. However, as Jody points out, “If that’s not true in your family, it kind of doesn’t matter.” There is a direct link between LGBTQ teen homelessness and a “lack of family acceptance,” says Jody. Adults like Anna, too, face challenges when hard times hit and they don’t always feel safe turning to family.

Service providers like Rochelle and Jody also recognize the progress still to be made in the homeless service communities. With 43 percent of clients served by homeless drop-in centers identifying as LGBTQ, there’s a major need for safe environments that serve LGBTQ communities. Rochelle believes that training staff can go a long way toward making an organization more welcoming for LGBTQ clients, setting the tone for respect and openness.

More compassion, more respect, more caring, and more concern

“For us, sexual and gender identity is as big a topic as race,” Rochelle says. “We need to start educating our staff; we need to give them a vocabulary. It’s through conversation that we learn.”

Time is changing the overall attitude toward the LGBTQ community, but queer youth and adults like Anna — and particularly queer people of color — continue to find themselves on the streets. Jody points out that some recent legislative changes, like extending foster care to age 21, are steps in the right direction, but ending homelessness requires further government action. The sheer difficulty of getting an ID card can be an overwhelming barrier for homeless youth without family contact, and prevalent policies regarding criminal records make employment nearly impossible for many. The housing, medical, and education bureaucracies can be even worse for queer youth and adults.

But Rochelle and Anna both say that the answer starts with people rather than policy. Anna believes that we can prevent people from repeating her experiences with “more compassion, more respect, more caring, and more concern.”

Rochelle agrees, adding, “as long as we keep humanity at the forefront, we’ll be all right.”

Learn more

– Listen to this recent PRX story about homeless LGBTQ Mormon youth in Utah and a program that serves them (click on Segment B).

– Read “Participating and Proud,” a five-part Firesteel blog series about the housing challenges that the LGBTQ community faces.

– Watch this video about LGBTQ youth homelessness from In The Life Media:

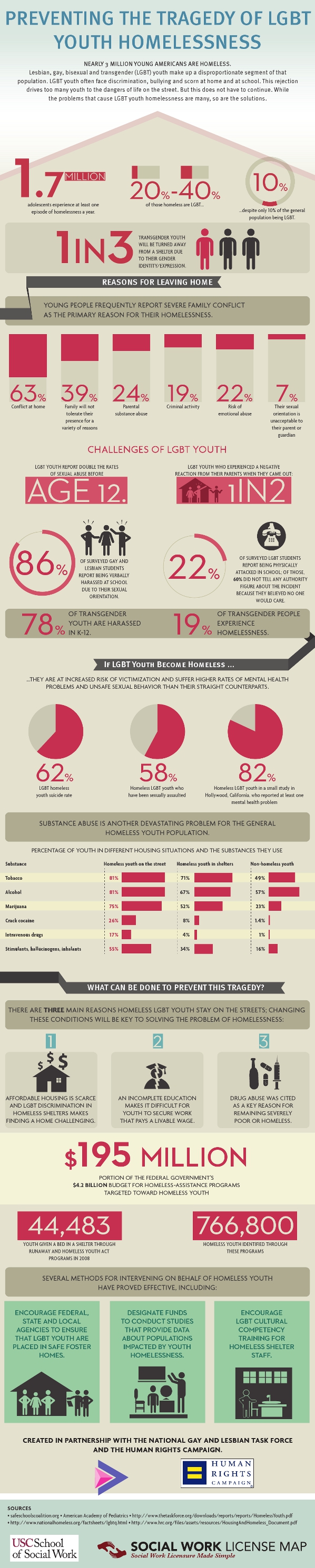

– Check out this infographic from the USC School of Social Work:

Pingback: A Year of Service: We’ll Miss You, Sarah! | Volunteer with YWCA Seattle | King | Snohomish()

Pingback: ¿Por qué no existe una 'marcha del orgullo heterosexual'? | ePiQly()